1. INTRODUCTION

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) or Lactobacilli are Gram-positive, low-GC, acid-tolerant, generally nonsporulating, no respiring, either rod- or coccus-shaped bacteria, and are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) [1]. It is ribosomal synthesized cationic peptides that are produced by almost all groups of bacteria and were discovered by Gratia in the year 1925 and named colicin [2]. It was reported that it is very potent and shows antimicrobial activity against other closely related species but is immune to the producer cells [3]. So far, nisin is the only commercially produced food-grade bacteriocin utilized as a preservative for a variety of food products, possessing FDA-approved GRAS status for certain applications. There are never any encouraging reports that have been found, where nisin has been combined with multi-bacteriocin-producing bacteriocin to effectively control foodborne pathogens [4].

Research is also being done on derivatives with improved activity and inhibition spectrum [5], as well as derivatives with increased resistance to proteolytic enzymes (which is not necessarily accompanied by superior activity) [6]. When compared to the peptides produced by eukaryotic cells, which typically have 102–103-fold lower activities, bacteriocins are active and show strong action even at nanomolar concentration [7]. The latest classification arranges bacteriocins into three major classes based on their structural and physicochemical properties [8]. As reported, generally bacteriocins need not be defined as amphipathic, positive, or cationic, since there are anionic bacteriocins such as subtilosin [9]. These include a wide spectrum of biological activities and their mode of action is hotly debated. They include modest to large molecular mass compounds as well as simple, unmodified peptides, and peptides that have undergone extensive post-translational modification.

Although the fundamental process is still unknown, a few investigations have documented the precise way that bacteriocin affects target cells. Class II bacteriocins also function to damage the target cells’ integrity of their membranes [10]. Other bacteriocins like Carnocyclin A are voltage-dependent, anion-selective show specific activity and are narrowed down based on their ability to form pores in lipid membranes [11]. Extremely high concentrations of AS-48 and Carnocyclin A permeabilize liposomes and/or lipid bilayers without the need for a receptor. Circular bacteriocins of this type are thought to act specifically; to kill cells, they must bind and target a specific receptor. It is, therefore, much stronger (about 1000-fold) than the derived eukaryotic antibacterial peptides [12]. Few leaderless bacteriocins belong to the M50 family and target zinc-dependent membrane-bound protease [13] as well as the two-peptide bacteriocins enterocin 1071 and lactococcin G target decaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatase UppP (a membrane protein involved in peptidoglycan synthesis) [14].

A report has also been made on antibacterial activity by different Lactobacillus sp. against a varied pathogenic strain. Cell-free supernatant (CFS) extracted from lactobacillus acted against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, and Citrobacter freundii, with an inhibition zone diameter of 17 mm [15]. The antibacterial activity of Lacticaseibacillus casei and Lactobacillus plantarum was checked against E. coli, Salmonella typhi, S. aureus, Shigella dysenteriae, Bacillus anthracis [16]. In addition, nine Lactobacillus strains were isolated and checked its activity against human pathogens like Candida albicans (ATCC 44831), Enterococcus faecium (ATCC 51558), Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 12228), Propionibacterium acnes (ATCC 6919), E. coli (ATCC 29181), Shigella sonnei (ATCC 25931), and Helicobacter pylori (ATCC 43579), Nitrobacter cloacae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Listeria monocytogenes as reported [17].

The activity of EPS of L casei was also examined, which showed to inhibit the biofilms of B. cereus, S. aureus, S. typhimurium, and E. coli O157:H7, with the highest inhibition ratios of 95.5% ± 0.1%, 30.2% ± 3.3%, 14.3% ± 0.6%, and 16.9% ± 5.4%, respectively [18].

The anti-microbial peptide (AMP) pleurocidin is present in the Atlantic flounder species known as the winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus). Pleurocidin, one of these AMPs, is effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The peptide has been found to have potent anti-cancer effects on human cancer cells. Research on pleurocidin may result in the creation of novel cancer and antibiotic-resistant bacteria treatment modalities. Because some of the bacteria that are susceptible to it are also fish diseases, it is feasible that the peptide can be employed as a medical remedy for fish species [19].

This study focused on the search for novel bacteriocin-producing LAB which is generally recognized as a safe (GRAS) organism. The necessity of this work is to target the global issue in the name of cancer with the use of this bacteriocin extracted from this GRAS organism without minimal side effects on the patient health.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample Collection

Dairy products such as milk and curd, as well as vegetables like cucumber and cabbage and other samples including appam batter, rice wine, cumin, corn, and fennel seeds, were all fermented at room temperature without the addition of any starting culture. From January to November 2017, additional handmade samples, including sauerkraut and tempeh, were also made for the screening of bacteriocin-producing LAB. All the samples were collected from the Vellore district.

2.2. Sample Preparation

To isolate bacteria, 1 mL of dairy samples like curd and milk and food samples such as rice, wine, and appam batter were inoculated in 100 mL of skim milk broth and kept for 24–48 h at 30°C. Finally, 1 mL of cultured skim milk broth of 48 h was inoculated in De man rogosa and Sharpe agar media (MRS) broth. All the vegetable samples were washed thoroughly, chopped, and kept in saline water for 6–7 days. Cumin was directly dissolved in skim milk broth and kept for 7–14 days at 30°C. Simultaneously, 1 mL was transferred from each sample and inoculated in skim milk media as a growth media for LAB, which were finally inoculated in MRS broth [20].

2.3. Screening and Biochemical Characterization of LAB

Bacterial colonies with different morphologies were selected and subjected to preliminary screening such as Gram staining and catalase test, H2O2, that is, oxidoreductase (E, C, 1, 11, 1, 6). The Gram-positive and catalase-negative pure isolates were all freshly streaked onto MRS agar plates, consisting of 0.1% calcium carbonate and were incubated at 30°C for 24–48 h [21]. Characterization of both cocci, rod, Gram-positive, and catalase negative isolates was later subjected to the MR-VP test [22].

2.4. Screening for Bacteriocin-producing LAB

Positive isolates which showed a clear zone on MRS-Calcium carbonate plates were subjected to agar well diffusion assay (AWDA) to screen for bacteriocin-producing LAB. Initially, 1 ml of the isolates were freshly inoculated in 100 mL of MRS broth and kept for incubation at 30°C for 48 h. After completion of 12 h of incubation, for every 6 h, 20 mL of the culture was collected and centrifuged (13,000 × g, 4°C, 20 min). The CFS was sterilized by passing through a 0.2 μm pore size filter (Acrodisc1 with Super membrane, Pall Corp., USA). L. monocytogenes Microbial type cell culture 5260 (MTCC 5260), as an indicator organism, was cultured overnight in brain heart infusion broth and diluted with normal sterilized water to a final concentration of approximately 1 × 108 CFU/mL. Sterile MRS broth was used as negative control and antibiotic ampicillin concentration of 1 mg/mL as a positive control. The plates were incubated at 30°C overnight and a clear zone of inhibition was observed within the next 24 h. The assay was performed in triplicate for at least two independent experiments and the average value was reported [23]. The assay was continued for more than 60 h and simultaneously the activity was checked to access the rate of production of bacteriocin.

2.5. Antibacterial Activity

Standard pathogenic bacterial cultures used are L. monocytogenes MTCC 5260, E. coli MTCC 2089, S. aureus MTCC 5257, Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 2242, S. typhi MTCC 2501, were procured from MTCC and sub-cultured at regular intervals [24]. CFSs of LAB were obtained after centrifugation (12,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) and were further heated at 75°C for 15 min to kill the proteolytic enzymes present and the bacteriocin activity assay was carried out using AWDA. The clear zone of inhibition was observed within 24 h [25]. Positive isolates VITRW02, VITRW04, VITCM05, and VITCU07 were checked for their antibacterial activity against the pathogenic organism, the concentration of 108 CFU/mL. The diameter of the zone of inhibition was used to measure the antibacterial activity [26].

2.6. Determination of Bacteriocin Activity against L. monocytogenes

The arbitrary unit (AU/mL), which is the reciprocal of the highest dilution that inhibits the growth of the indicator strains, was used to express the activity. The AU of antibacterial activity per milliliter was defined as  . The titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution (2n) that resulted in inhibition of the indicator lawn. Where n = Reciprocal of the highest dilution, V = Sample volume loaded into the well. At least two independent experiments were performed with the test in triplicate and the average value was reported. Further, the activity was expressed in international unit IU/mL, using Nisin (10000 IU) as stock. The standard curve of free nisin was plotted, with inhibition zone (mm2) on X-axis against concentration (mg/mL) on Y -axis. The protein concentration was estimated by Lowry’s method using BSA (1 mg/mL) as the standard protein. The O.D has been recorded at 660 nm in ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry [27].

. The titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution (2n) that resulted in inhibition of the indicator lawn. Where n = Reciprocal of the highest dilution, V = Sample volume loaded into the well. At least two independent experiments were performed with the test in triplicate and the average value was reported. Further, the activity was expressed in international unit IU/mL, using Nisin (10000 IU) as stock. The standard curve of free nisin was plotted, with inhibition zone (mm2) on X-axis against concentration (mg/mL) on Y -axis. The protein concentration was estimated by Lowry’s method using BSA (1 mg/mL) as the standard protein. The O.D has been recorded at 660 nm in ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry [27].

2.7. Identification of Bacteria

The isolate VITCM05 was subjected to biochemical characterization such as indole, nitrate reductase, citrate utilization, and oxidase test [28] and the morphology of the LAB VITCM05 was captured using a scanning electron microscope in 18.99 K X magnification. Finally, the strain VITCM05 was identified by 16S rRNA molecular sequencing. Initially, the bacterial DNA was extracted and amplified using PCR, its product was later compared with known 16S rRNA gene sequences in GenBank by multiple-sequence alignment using the CLUSTAL W program. Subsequently, 16S rRNA molecular sequencing was performed as described by Labbe et al., [29] using the forward Primer 8F (5’AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG3’) and the reverse primer 1541R (5’AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA3’), followed by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) homology searching using the NCBI database.

2.8. Partial Characterization of Bacteriocin

2.8.1. Effect of pH and temperature

The AWDA was used to determine the bacteriocin activity. The pH of the supernatant was varied with 1N HCl and 1N NaOH. The pH of the supernatant was adjusted from pH 3 to pH 7. The supernatant was heated in a varied setup at various temperatures, including 37°C, 60°C, and 100°C for 120 min and 121°C for 15 min [21,30].

2.8.2. Effect of catalase and proteinase K and trypsin

The CFS was mixed with 100 μL of catalase and adjusted to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL. It was allowed to keep at room temperature without any disturbance in dark. The activity was determined by AWDA [31].

The CFS was subjected to proteolytic activity. To confirm it to be a proteinaceous compound, it was treated within a range of 1 mg/mL to 5 mg/mL of proteolytic enzymes such as proteinase K and trypsin (EC 3.4.21.4) (Sigma- Aldrich Corporation, USA) at 4°C for 24 h. The activity was determined by AWDA [32].

2.8.3. Storage condition

The stability of the extracted bacteriocin was checked at varied temperatures for 3 months at 4°C, −20°C, 37°C and AWDA was used to measure activity [33].

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Screening and Biochemical Characterization of LAB

In this present research, 110 isolates were obtained from various fermented food samples. Preliminary assays such as Gram’s staining and catalase test were performed. Gram-positive and catalase-negative isolates are assumed to be LAB and taken for further assays.

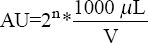

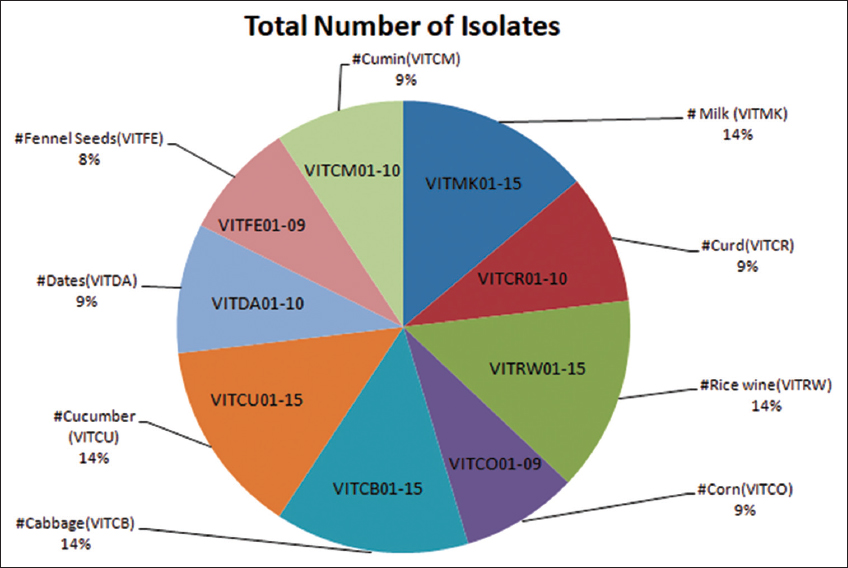

In this study, 15 isolates were obtained from fermented samples such as milk, cabbage, rice, wine, and cucumber and 10 isolates were obtained from each of the samples such as fermented dates, curd, and cumin. Whereas the least number of isolates, that is, nine isolates were obtained from fermented corn samples and fennel seeds, as shown [Figure 1]. Among 110 isolates only 38 isolates were found to be LAB based on the calcium hydrolysis assay. The isolates VITCU07, VITCM05, VITRW02, and VITRW04 showed Methyl red positive and Voges Proskauer negative as shown [Figure 2].

| Figure 1: Screening and biochemical characterization of lactic acid bacteria [Click here to view] |

| Figure 2: The isolates (a)VITCM05, b) VITRW04, (c)VITRW02, (d)VITCU07 which showed hydrolysis of calcium carbonate, are shown respectively, (e) Methyl Red positive (f) Voges-Proskauer Negative. [Click here to view] |

3.2. Screening for Bacteriocin-producing LAB

The selected isolates which showed a clear zone of hydrolysis in the calcium carbonate hydrolysis assay have been confirmed to be a lactic acid bacterium. This states that organic acid produced by the LAB hydrolyses the calcium carbonate, thus producing a halo zone. A similar result has also been reported by Nurindasari et al. [34] when calcium carbonate was added to the MRS agar medium, LAB showed a clear zone of hydrolysis. Among the 110 isolates, 41 were able to hydrolyze calcium carbonate within 24–48 h of incubation. The isolates VITCF07, VITCM05, VITRWO2, VITRW02, VITRW04, VITCR08, VITCM03, and VITMK04 were found to be the potent ones with the prominent zone of hydrolysis [Figure 2].

3.3. Antibacterial Activity

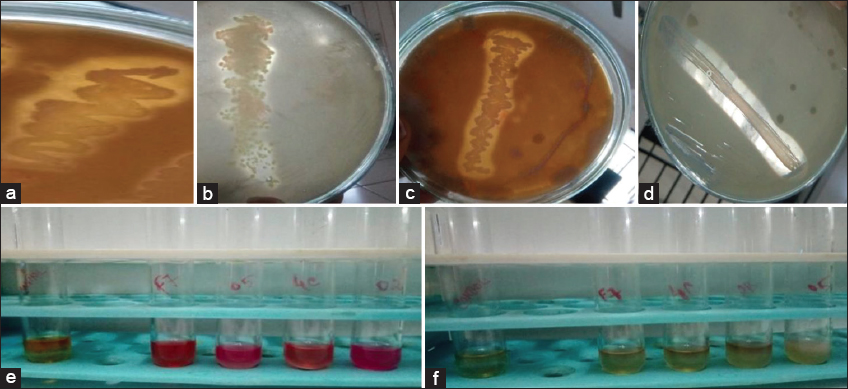

The rate of production of bacteriocin for the four major isolates was accessed using an AWDA, against the indicator organism L. monocytogenes. As reported by Niederhausern et al., they collected the sample at regular intervals and evaluated its optical density and bacteriocin production. Compared to that study, similar work has been carried out in this research [35]. The growth of the bacteria was found to be directly proportional to the production of bacteriocin.

The isolate VITCU07 produced bacteriocin at 48th h before its stationary phase reached 60th h. Whereas the strain VITCM05 VITRW04 and VITRW02 secreted bacteriocin on 36th h, in its late exponential phase and reached its late stationary phase at 48th h where the production rate was found to be the highest. The isolate VITCF07 showed its activity on 42nd h with 15 mm of a zone of inhibition. Moreover, the highest zone was obtained at 48th h with 18 mm of diameter. In addition, it was also evident, that on 54th h, the diameter was gradually reduced to 16 mm in width.

The isolates VITCM05, VITRW02, and VITRW04 reached their late exponential phase on 36th h, with 10 mm, 12 mm, and 8 mm of a zone of inhibition, respectively. Apart from that, it was observed for the isolates VITCM05, VITRW02, and VITRW04, the production rate was high on 48th h with 18 mm, 14 mm, and 12 mm of a zone of inhibition, respectively. Finally, the late stationary phase was observed on 54th h with no zone of inhibition. Based on the evidence, the hour of production was detected and following that, the bacteriocin was extracted to carry out further assays. The graph depicts the optimum production hour of the bacteriocin extracted from the isolates VITCU07 (blue line), VITCM05 (red line), VITRW02 (green line), and VITRW04 (violet line). The graph shows the growth of the bacterial culture (an hour) on the X-axis, versus the production of bacteriocin based on the zone of inhibition (mm) on the Y-axis shown [Figure 3].

| Figure 3: Production hour portrayed using graphical illustration. VITCU07, VITCM05, VITRW04 and VITRW02 showed respectively. [Click here to view] |

The isolates VITCM05 and VITRW04 18 mm, VITRW02 16 mm, and VITCU07 with 12 mm each showed activity against other pathogens in addition to antilisterial activity. Against E. coli VITCM05 showed 16 mm, VITRW02 15 mm, VITRW04 14 mm, and VITCU07 showed a 12 mm zone of inhibition. VITCM05 showed a 15 mm and VITRW04 18 mm zone of inhibition whereas VITRW02 and VITCU07 failed to inhibit the growth of the pathogen P. aeruginosa, a common encapsulated organism. All the isolates VITCM05, VITRW04, VITRW02, and VITCU07 were able to inhibit S. typhi, with a good zone of inhibition of 15 mm, 12 mm, 14 mm, and 8 mm, respectively. S. aureus is the most common food-borne pathogen was inhibited by the isolates VITRW02, and VITCM05 with a zone of 10 mm, whereas VITCU07 and VITRW04 produced a slight decrease in a zone of inhibition when compared to the rest of the isolates, with 6 mm and 8 mm of the zone. The work can be compared with the report of Nghe and Nguyen, where Pediococcus pentosaceus (VTCC-B-601) showed a good zone of inhibition of 19.67 ± 0.58 in their late exponential phase against S. typhi, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus [36].

The major four isolates, however, were found to inhibit L. monocytogenes, when compared to the strain VITCM05. The isolate VITRW04 demonstrated a modest zone of inhibition against all pathogens while exhibiting the maximum zone of inhibition solely against L. monocytogenes. The isolates VITRW02 and VITCU07 did not exhibit any activity against Pseudomonas sp. Comparatively, VITCM05 showed very good activity against E. coli, S. typhi, and P. aeruginosa other than L. monocytogenes as shown [Table 1]. A similar finding has also been reported earlier, where the major role of the potent probiotic strains has been explored using AWDA against food-borne pathogens [37-39].

Table 1: The antibacterial activity of the isolates against the pathogen against L. monocytogenes (c) E. coli (d) P. aeruginosa (e) S. typhi (f) S. aureus are presented.

| S. No. | Isolates | E. coli | L. mono-cytogenes | P. aeruginosa | S. typhi | S. aureus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | VITCF07 | 12 | 12 | - | 8 | 6 |

| 2. | VITCM05 | 16 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 10 |

| 3. | VITRWO2 | 15 | 16 | - | 14 | 10 |

| 4. | VITRW04 | 14 | 18 | 18 | 12 | 8 |

Zones are given in (mm), mean values are given (assays were done in triplicate). SD±0.25; P ≤ 0.5. Listeria monocytogenes: L. monocytogenes, Escherichia coli: E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa: P. aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi: S. typhi, Staphylococcus aureus: S. aureus

3.4. Determination of Bacteriocin Activity against L. monocytogenes

The protein concentration of the CFS of the isolate VITCM05 was estimated by Lowry’s method and it was found to be 3.4 mg/mL. As reported by Ramalingam et al., they estimated the protein content for the crude bacteriocin using Lowry’s method and was found to be 63.7 µg/mL. In this regard, the present study has obtained a better content of protein when compared to the research of Ramalingam et al. [40]. In addition, the research by Qiao et al. revealed that the bacteriocin activity was 816.87 ±5.21 AU/mL after being optimized, compared to the current work, before any optimization the activity was found to be 800 AU/mL [41]. The zone of inhibition was found to be 18 mm, so the A =πr2 was calculated to be 254.47 mm2. Based on the area of the zone of inhibition, the concentration of the nisin (μg/mL) was found to be 50 μg/mL. Using the conversion IU - 0.025 μg, the bacteriocin activity was determined to be 2000 IU/mL.

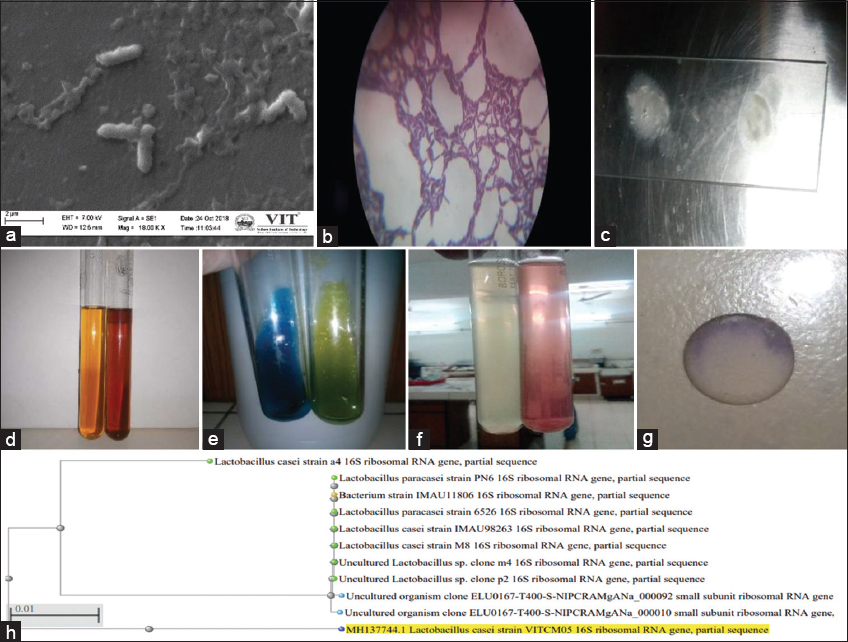

3.5. Identification of Bacteria

The strain VITCM05 was identified as rod-shaped (12.5 mm in width), under a scanning electron microscope with 18.00 KX magnification Gram-positive bacteria under a compound microscope with ×40 magnification and catalase negative as shown [Figure 4a-c]. The isolate was able to decompose or reductive deaminate tryptophan to indole with the help of the intracellular enzyme present called tryptophanase. The accumulation of the indole on reaction with Kovac’s Reagent turns the color from yellow to cherry red. As the positive test, the ring as the oily layer can be seen at the top of the broth [Figure 4d]. The citrate utilization test is shown [Figure 4e]. The isolate was able to thrive in the media by converting citrate to pyruvate by citrate-permease and inorganic ammonium salts (NH4H2PO4) to ammonia. The pyruvate as the intermediate of the Kreb cycle enters the metabolic cycle of the bacteria and is used as energy currency. Whereas the ammonium salts are broken down to ammonia which gives an alkaline environment to the media with a pH of 7.6. Hence, the indicator in the media bromthymol blue turns green. The nitrate reduction test was found to be positive as shown [Figure 4f]. The isolate was able to reduce nitrate to nitrite with the production of nitrate reductase enzyme on the addition of sulfanilic acid and a-naphthylamine; consecutively, it gives a red precipitate (prontosil), a water-soluble azo dye that can be observed in the broth. In the case of the oxidase test, the bacteria when inoculated on the filter disk impregnated with tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride were able to produce enzyme cytochrome oxidase, which, in turn, the disk oxidized to purple color as shown [Figure 4g]. The sequence of the strain L. casei was submitted to the NCBI gene bank database under accession No: MH137744. Using BLAST, it showed 93% maximum identity and E-value equal to 0 for all closely related taxa. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the distance tree of NCBI followed by BLAST pairwise alignments software as shown [Figure 4h]. This report can also be compared with the data produced by Sharma et al. [42].

| Figure 4: The images showed (a) Rod Shaped, (b) Gram positive, (c) catalase test negative with no bubble formation, (d) indole test, (e) citrate test, (f) nitrate reduction test, (g) oxidase test, (h) phylogenetic tree: The image is showing the relationship between the 16S rDNA gene sequences VITCM05 with five different Lactobacillus species, one bacterium strain, two uncultured lactobacillus and uncultured organism clone. The bar indicates 0.01 substitutions per nucleotide position. [Click here to view] |

3.6. Partial Characterization of Bacteriocin

3.6.1. Effect of pH and temperature

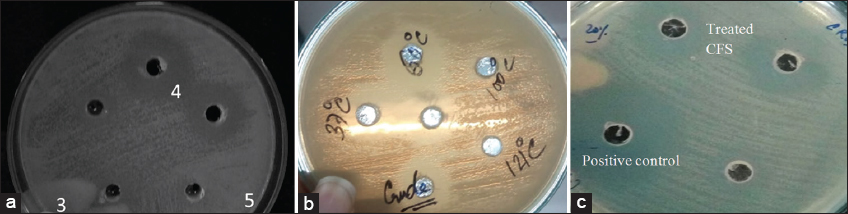

The pH of the crude bacteriocin was altered using 0.1HCl and 0.1 NaOH from pH 3–7, and the activity of the bacteriocin was found to be very much effective at the low pH range from pH 3–5. The zone of inhibition of 18 mm was produced against the aliquots of pH 3, 4, and 5. For pH 6 and 7, almost negligible or no zone of inhibition could be detected. Due to its excellent thermal stability, the CFS maintained its activity at 60°C and 100°C but failed to do so at 121°C, as shown [Figure 5a and b]. With an increase in pH, it was seen that the antibacterial activity considerably decreased. It might be because, as described and explored by Jiang et al., strong intramolecular electrostatic interactions at extreme pH values result in a partial or complete loss of activity [43]. The bacteriocin in our investigation was able to tolerate the high intramolecular electrostatic interactions, and as a result, showed a strong activity even at the low pH. This may be deduced by comparing the data of pentocin JL-1 which showed activity even at pH 2 with 65.69% of antibacterial activity, which indicate its usefulness in most food [44].

| Figure 5: (a) Effect of pH range from 3 to 7, (b) Effect of temperature, (c) Effect of catalase has been showed. [Click here to view] |

3.6.2. Effect of catalase, proteinase k and trypsin

Following catalase treatment, the CFS maintained the activity, with a distinct zone of inhibition as depicted [Figure 5c]. This shows how catalase produced by L. casei, converted H2O2 into water and oxygen. As a result, the zone is solely by the bacteriocin and not by H2O2. Similar to the present work, Fossi et al. have performed a catalase test to screen LAB, and they found 12 catalase-negative and Gram-positive isolates obtained from the “Gari” sample [45].

The bacteriocin activity was completely lost when treated with trypsin, whereas on treatment with proteinase K, the activity was retained. However, in the case of proteinase K, it cleaves peptide bonds in proteins next to the carboxyl group of hydrophobic amino acid residues (aliphatic and aromatic). Hence, it confers that the bacteriocin in presence of proteinase K, retained its activity due to the absence of coarse detergent, high temperature, or salts. The observed result confers, the bacteriocin to be peptide in nature, as trypsin catalyzes the hydrolysis of peptide bonds and so it completely lost its activity, with no zone of inhibition against the pathogen. As stated by Sharma and Yadav, bacteriocin-like protein has their limitation in being sensitive to proteolytic enzymes. To justify, the obtained metabolite was proteinaceous in nature and are bacteriocin-like substance exerting a similar property; hence, this preliminary characterization was indeed necessary [46].

3.6.3. Storage condition

At 37°C, the bacteriocin completely lost its activity after 24 h. The extracted bacteriocin retained its activity by 100% when kept at 4°C and −20°C. It showed this novel bacteriocin to be better than the BLIS activity as reported by Md Sidek et al. [44] where the activity only remained constant for a month. Further in our research, the CFS stored at 4°C completely lost its activity after 3 months but at −20°C, it retained its activity with a 20% reduction. Similar reports stated 80% of reduction in the activity after 3 months at 4°C and −20° C. Thus, it may be inferred that chilling items are necessary to keep them functioning for a prolonged time. In addition, it can be stated since it is a protein, it maintains its natural structure and folds when stored at low temperature. Moreover, it retained its activity when stored at −20°C after lyophilization for 6 months.

4. CONCLUSION

The isolate VITCM05, which was later identified as L. casei, had a broad range of antibacterial action against the major pathogens. The proteinaceous metabolite was discovered to be stable at −20°C for more than months. The bacteriocin was discovered to be a promising agent in this study as an antibacterial agent in addition to being an anti-cancer agent as previously published. The future research can further explore this proteinaceous substance’s impact on the health sector. Due to the fact, cancer is still one of the leading diseases worldwide, this study has been conducted with A549 lung cancerous cell lines to explore the anti-cancer role and mechanism underlying the apoptotic activity.

5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to the VIT management for their continued support to carry out this research.

6. AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit it to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

7. FUNDING

This work was financially supported by Vellore Institute of Technology.

8. CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

9. ETHICAL APPROVALS

This study does not involve experiments on animals or human subjects.

10. DATA AVAILABILITY

Data are available on request to the corresponding author.

11. PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

12. CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The authors give consent to participate.

REFERENCES

1. Tashakor A, Hosseinzadehdehkordi M, Emruzi Z, Gholami D. Isolation and identification of a novel bacterium,

2. Gratia JP, Andre Gratia:A Forerunner in Microbial and Viral Genetics. Genetics 2000;156:471-6. [CrossRef]

3. Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Bacteriocins:Developing innate immunity for food. Nat Rev Microbiol 2005;3:777-88. [CrossRef]

4. Mills S, Griffin C, O'Connor PM, Serrano LM, Meijer WC, Hill C,

5. Field D, Begley M, O'Connor PM, Daly KM, Hugenholtz F, Cotter PD,

6. O'Shea EF, O'Connor PM, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. Synthesis of trypsin-resistant variants of the listeria-active bacteriocin salivaricin P. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010;76:5356-62. [CrossRef]

7. Noroozi E, Tebianian M, Taghizadeh M, Dadar M, Mojgani N. Anticarcinogenic potential of probiotic, postbiotic metabolites and paraprobiotics on human cancer cells. In:Probiotic Bacteria and Postbiotic Metabolites:Role in Animal and Human Health. Vol. 02. 2021. 153-77. [CrossRef]

8. Zacharof MP, Lovitt RW. Bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria a review article. APCBEE Procedia 2012;2:50-6. [CrossRef]

9. Mathur H, Rea MC, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. The sactibiotic subclass of bacteriocins:An update. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2015;16:549-58. [CrossRef]

10. Stevens KA, Sheldon BW, Klapes NA, Klaenhammer TR. Nisin treatment for inactivation of

11. Gong X, Martin-Visscher LA, Nahirney D, Vederas JC, Duszyk M. The circular bacteriocin, carnocyclin A, forms anion-selective channels in lipid bilayers. Biochim Biophy Acta 2009;1788:1797-803. [CrossRef]

12. Steinstraesser L, Kraneburg U, Jacobsen F, Al-Benna S. Host defense peptides and their antimicrobial-immunomodulatory duality. Immunobiology 2011;216:322-33. [CrossRef]

13. Uzelac G, Kojic M, Lozo J, Aleksandrzak-Piekarczyk T, Gabrielsen C, Kristensen T,

14. Kjos M, Oppegård C, Diep DB, Nes IF, Veening JW, Nissen-Meyer J,

15. Rashti Z, Koohsari H. Antibacterial effects of supernatant of lactic acid bacteria isolated from different Dough's in Gorgan city in North of Iran. Integr Food Nutr Metab 2015;2:193-6. [CrossRef]

16. Amin M, Jorfi M, Khosravi AD, Samarbafzadeh AR, Sheikh AF. Isolation and identification of

17. Shokryazdan P, Sieo CC, Kalavathy R, Liang JB, Alitheen NB, Jahromi MF,

18. Xu X, Peng Q, Zhang Y, Tian D, Zhang P, Huang Y,

19. McMillan KA, Coombs MR. Investigating potential applications of the fish anti-microbial peptide pleurocidin:A systematic review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;14:687-700. [CrossRef]

20. Liu W, Bao Q, Qing M, Chen X, Sun T, Li M,

21. Chen YS, Wu HC, Pan SF, Lin BG, Lin YH, Tung WC,

22. Islam KN, Akbar T, Akther F, Islam NN. Characterization and confirmation of

23. Ye P, Wang J, Liu M, Li P, Gu Q. Purification and characterization of a novel bacteriocin from

24. Bhagat D, Raina N, Kumar A, Katoch M, Khajuria Y, Slathia PS,

25. Zamfir M, Callewaert R, Cornea PC, Savu L, Vatafu I, De Vuyst L. Purification and characterization of a bacteriocin produced by

26. Yang E, Fan L, Jiang Y, Doucette C, Fillmore S. Antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from cheeses and yogurts. AMB Express 2012;2:48. [CrossRef]

27. Zhu X, Zhao Y, Sun Y, Gu Q. Purification and characterisation of plantaricin ZJ008, a novel bacteriocin against

28. Venkatachalam P, Selvakumar DD, Muthukumar J. Assessing of antilisterial compounds from

29. LabbéN, Juteau P, Parent S, Villemur R. Bacterial diversity in a marine methanol-fed denitrification reactor at the Montreal Biodome, Canada. Microb Ecol 2003;46:12-21. [CrossRef]

30. Udhayashree N, Senbagam D, Senthilkumar B, Nithya K, Gurusamy R. Production of bacteriocin and their application in food products. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2012;2:S406-10. [CrossRef]

31. Chen J, Pang H, Wang L, Ma C, Wu G, Liu Y,

32. De Giani A, Bovio F, Forcella M, Fusi P, Sello G, Di Gennaro P. Identification of a bacteriocin-like compound from

33. Malini M, Savitha J. Heat stable bacteriocin from

34. Nurindasari A, Bukang S, Ananda M, Suwastika IN. Bacteriocin from Donggala cow's milk againts

35. de Niederhäusern S, Camellini S, Sabia C, Iseppi R, Bondi M, Messi P. Antilisterial activity of bacteriocins produced by lactic bacteria isolated from dairy products. Foods 2020;9:1757-68. [CrossRef]

36. Nghe D, Nguyen T. Characterization of antimicrobial activities of

37. Anandharaj M, Sivasankari B. Isolation of potential probiotic

38. Riboulet-Bisson E, Sturme MH, Jeffery IB, O'Donnell MM, Neville BA, Forde BM,

39. Messaoudi S, Manai M, Kergourlay G, Prévost H, Connil N, Chobert JM,

40. Ramalingam C, Jain H, Vatsa K, Akhtar N, Mitra B, Vishnudas D,

41. Qiao X, Du R, Wang Y, Han Y, Zhou Z. Isolation, characterisation and fermentation optimisation of bacteriocin-producing

42. Sharma A, Lee S, Park YS. Molecular typing tools for identifying and characterizing lactic acid bacteria:A review. Food Sci Biotechnol 2020;29:1301-18. [CrossRef]

43. Jiang H, Zou J, Cheng H, Fang J, Huang G. Purification, characterization, and mode of action of pentocin JL-1, a novel bacteriocin isolated from

44. Md Sidek NL, Halim M, Tan JS, Abbasiliasi S, Mustafa S, Ariff AB. Stability of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by

45. Fossi BT, Ndjouenkeu R. Probiotic potential of thermotolerant lactic acid bacteria isolated from “Gari “a cassava-based African fermented food. J Appl Biol Biotechnol 2017;5:001-5.

46. Sharma P, Yadav M. Enhancing antibacterial properties of bacteriocins using combination therapy. J Appl Biol Biotech 2022. Online First. https://doi.org/10.7324/JABB.2023.110206