1. INTRODUCTION

The accelerated growth of the population worldwide results in growing levels of food inadequacy. To overcome this issue, food production needs to be enhanced to satisfy the food requirements of the growing population. In view of this, exploration, identification, and utilization of less known leafy vegetables could play a prominent role in alleviating the hunger of the world’s expanding population [1]. Further, traditional leafy vegetables, being highly nutritive, play a crucial role during times of famine and poor harvest in ensuring food security [2]. Many unexplored leafy vegetables with hidden nutritional and medicinal values exist in their natural habitat that needs commercialization to solve the menace of malnutrition. Leafy vegetables not only add variety and flavor to our diet, but also meet our daily nutrient requirements. Due to their ready accessibility and lower price, they are regarded as “poor man’s vegetables,” thereby being identified as the food bowl of tribal and rural people. They also earn their livelihood by selling those leafy vegetables in the local market, boosting their socioeconomic standard. Unfortunately, they are considered inferior foods despite being a rich source of nutritional and medicinal values.

Leafy vegetables are excellent sources of minerals such as iron, magnesium, calcium, and potassium, along with Vitamins B, C, E, and K. Besides, they are bestowed with phytonutrients such as beta-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, and Omega-3 fatty acids, which protect cells from injury and age-related problems [3]. They are enriched in compounds that possess antidiabetic [4], anti-histaminic [5], and anti-carcinogenic properties [6]. Being enriched in folic acid, leafy vegetables fight anemia. Antioxidants in leafy greens protect against various diseases by scavenging free radicals in our body [7]. Due to the nutritional and therapeutic benefits of leafy vegetables, it can be explored as future herbal drugs and superfoods [8].

Leafy vegetables promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, forming a healthy gut microbiome. According to the earlier findings, sulfoquinovose, a sulfonated monosaccharide, found in many green vegetables supplies, a selective but crucial substrate for a few but widely distributed bacteria in the human gut [9]. This particular sort of sugar, which is utilized as an energy source by good gut bacteria as an energy source, increases their dominance and inhibits harmful bacteria from multiplying in the stomach [10]. Furthermore, as a good source of magnesium, leafy vegetables can help relieve constipation by increasing muscle contractions in our gastrointestinal tract. Further, it facilitates bowel movements by increasing water content in the intestines. They are low in calories and fat while being high in dietary fiber; they aid in weight loss and digestion. Thus, leafy greens boost our gut health, protecting us from gastrointestinal disorders.

Although several floristic and ethnobotanical studies on wild edible plants have been conducted in the state of Odisha [11-16], very little attempt has been made to document the diversity and ethnomedicinal uses of leafy vegetables in this region [17,18]. Despite the wide diversity of leafy vegetables in the Balasore district of Odisha, it is still unexplored by scientific communities. Therefore, the present study aims to identify, document and create a scientific database on leafy vegetables found in different blocks of the Balasore district, along with the determination of the most cited ethnomedicinally potent leafy vegetable used against gastrointestinal disorders.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Area

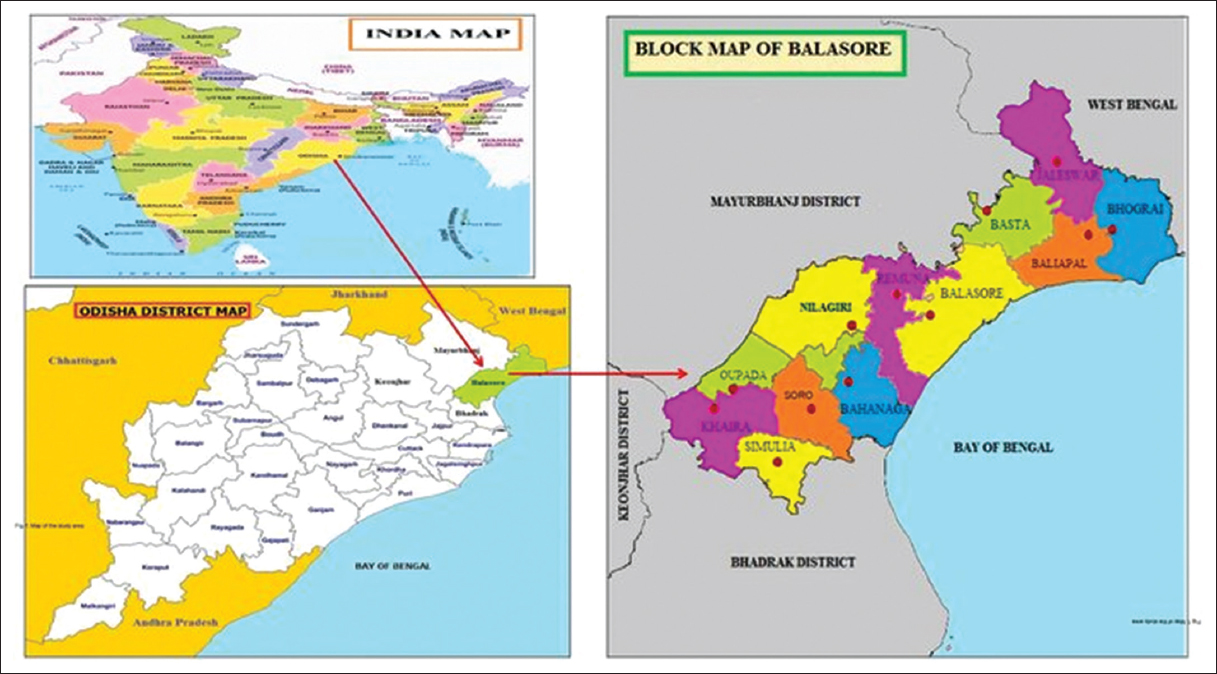

Balasore (latitude 21°3’–21°59’ N, longitude 86°20’–87°29’ E) is an administrative district which is located in the northern most coastal part of Odisha state, in Eastern India [Figure 1]. It is densely populated (92,320,529 people; 2011 census) and covers an area of 3806 km2. It is bordered on the North by the Midnapore district of West Bengal, on the East by the Bay of Bengal, on the South by Bhadrak district, and the West by Mayurbhanj and Keonjhar districts. Balasore and Nilagiri are the two administrative subdivisions, with 12 C.D. blocks: Jaleswar, Bhograi, Basta, Baliapal, Balasore, Remuna, Nilagiri, Bahanaga, Oupada, Soro, Khaira, and Simulia. It is known for its special tone of the local dialect, “Baleswari bhasa.” Besides, this district is inhabited by numerous ethnic, linguistic, religious groups, and indigenous tribes such as Santal, Bhumij, Oraon, etc. It is blessed with a good climate, alluvial soil, and perennial rivers that favor rich floral diversity in this region.

| Figure 1: Map of the study area. [Click here to view] |

2.2. Data Collection

Intensive seasonal field tours were conducted in the inner pockets of 12 blocks in the Balasore district of Odisha from April 2019 to March 2022. Through semi-structured interviews and discussions, information about the variety of leafy vegetables consumed by the district’s native and tribal people, along with their ethnomedicinal uses against gastrointestinal diseases, was gathered. During the survey, 216 local informants were interviewed, including 66% of men and 34% of women. The informants were between the ages of 28 and 80. Each plant’s data includes its botanical name, vernacular name, voucher number, family, habit, flowering, and fruiting season. The data for ethnomedicinal leafy vegetables comprise the botanical name, vernacular name, parts used, diseases treated, and mode of utilization.

2.3. Plant Identification and Collection of Voucher Specimens

By referring to the regional floras, plant specimens obtained during field visits were thoroughly studied taxonomically and identified [19-21]. Plants were photographed digitally in their natural habitat to facilitate their identification and nomenclature. The plant specimens were dried and kept as voucher specimens using herbarium techniques [22] and submitted as herbarium samples to the Department of Botany, School of Applied Sciences, Centurion University of Technology and Management, Odisha, India.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

With the help of biostatistical formulas, the factors of informant consensus (Fic) and fidelity level (Fl) of the most recorded (cited) leafy vegetables used against gastrointestinal diseases were calculated. The following equation calculated the Fic: Fic = Nur-Ntaxa/Nur-1, where Nur is the number of valuable reports in each category and Ntaxa is the number of species in each category [23,24]. The Fl was calculated for the most commonly reported medicinal leafy vegetables as: Fl (%) = (Np/N) × 100, where Np denotes the number of informants who claim to have used a plant species to treat a specific disease, and N denotes the number of informants who have used the plants as medicine to treat any given disease [25].

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

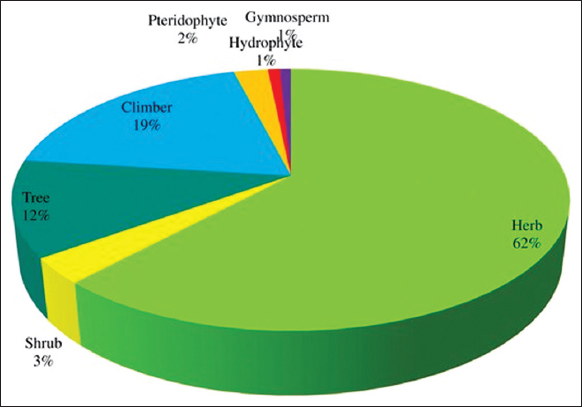

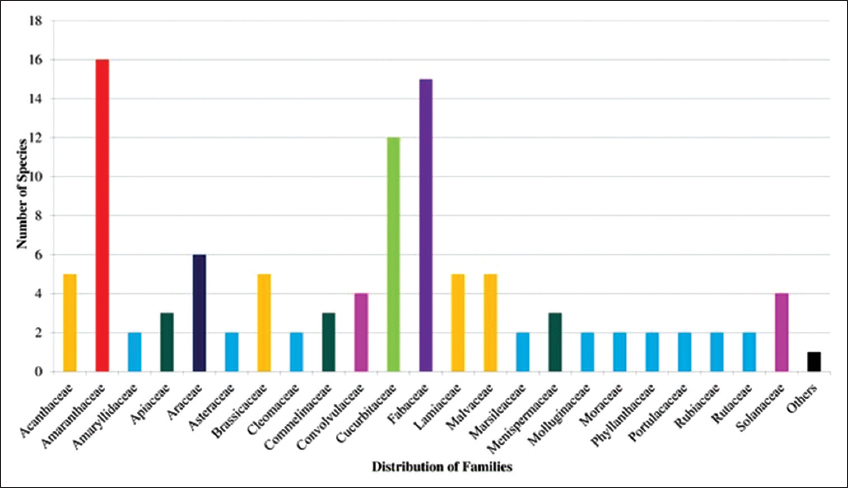

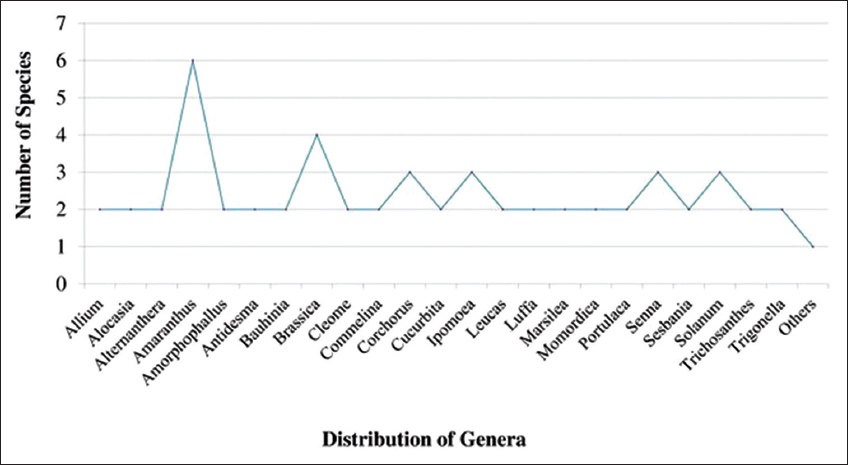

The study area recorded a total of 126 (122 angiosperms, 3 pteridophytes, and 1 gymnosperm) leafy vegetables belonging to 93 genera under 43 families [Table 1]. Among the 122 angiosperms recorded, 109 were dicot species belonging to 81 genera under 35 families, and 13 were monocot species belonging to 9 genera under 5 families. The distribution of leafy vegetables by habit revealed that 78 (62%) were herbs, followed by 24 (19%) climbers, 15 (12%) trees, 4 (3%) shrubs, 3 (2%) pteridophytes, 1 (1%) hydrophyte, and 1 (1%) gymnosperm [Figure 2]. Among the taxonomic families to which the documented leafy vegetables belong, Amaranthaceae with 16 species was observed to be dominant, followed by Fabaceae (15) and Cucurbitaceae with 12 species [Figure 3]. In contrast, Amaranthus with six species was reported to be the dominant genus [Figure 4]. A good number of less-known leafy vegetables, such as Abelmoschus moschatus Medik., Abutilon indicum (L.) Sweet, Achyranthes aspera L. Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. ex Schult., Antidesma ghaesembilla Gaertn., Bauhinia purpurea L., Bauhinia variegata (L) Benth., Cayratia auriculata (Roxb) Gamble, Celosia argentea L., Cleome viscosa L., Dicliptera bupleuroides Nees. and Telosma pallida (Roxb) W.G. Craib, etc. are consumed by the tribes of the Balasore district. Despite the fact that most of the species are grown as weeds, they are consumed as popular leafy vegetables by the tribal and rural belts of the Balasore district, revealing their hidden potential to combat malnutrition and hunger.

Table 1: Diversity of leafy vegetables in Balasore district of Odisha, India.

| S. No. | Botanical name | Vernacular name [O: Odia; B:Bengali] | Family | Voucher number | Habit | Flowering and Fruiting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abelmoschus moschatus Medik. | Bano bhindi (O) | Malvaceae | NN–363 | Herb | Aug–Jan |

| 2 | Abutilon indicum (L.) Sweet | Pedi–pedika (O) | Malvaceae | NN–395 | Herb | Jul–Apr |

| 3 | Achyranthes aspera L. | Apamaranga (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–298 | Herb | Oct–Feb |

| 4 | Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. ex Schult. | Paunsia (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–256 | Herb | Aug–Jan |

| 5 | Allium cepa L. | Piaja (O) | Amaryllidaceae | NN–305 | Herb | Feb–Apr |

| 6 | Allium sativum L. | Rasuna (O) | Amaryllidaceae | NN–277 | Herb | Feb–Apr |

| 7 | Allmania nodiflora (L.) R.Br. ex Wight | Chadheimundia Saga (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–380 | Herb | Jul–Dec |

| 8 | Alocasia fornicata (Kunth) Schott. | Dudh maan Kochu (B) | Araceae | NN–251 | Herb | Jun–Sep |

| 9 | Alocasia macrorrhizos (L.) G.Don | Mana Saru (O) | Araceae | NN–390 | Herb | Jul–Nov |

| 10 | Alternanthera philoxeroides ( Mart.) Griseb | Denga Madaranga (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–243 | Herb | Dec–Apr |

| 11 | Alternanthera sessilis (L.) R.Br. ex DC. | Chotta Madaranga (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–227 | Herb | Jul–Jan |

| 12 | Amaranthus blitum L. | Kosala (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–232 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 13 | Amaranthus caudatus L. | Khada Sago (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–295 | Herb | Jun–Oct |

| 14 | Amaranthus graecizans L. subsp. thellungianus (Nevski ex Vassilez.) Gusev | Champa neutiya (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–318 | Herb | Aug–Dec |

| 15 | Amaranthus spinosus L. | Kanta neutia (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–240 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 16 | Amaranthus tricolor L. | Lal Khada (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–235 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 17 | Amaranthus viridis L. | Leutiya (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–233 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 18 | Amorphophallus bulbifer (Roxb.) Blume | Dhala Oal (O) | Araceae | NN–353 | Herb | Jul– Aug |

| 19 | Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson | Olua (O) | Araceae | NN–388 | Herb | Apr–Jun |

| 20 | Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Nees | Bhuinimbo (O) | Acanthaceae | NN–396 | Herb | Sep–May |

| 21 | Antidesma acidum Retz. | Matha Saag (O) | Phyllanthaceae | NN–225 | Tree | May–Dec |

| 22 | Antidesma ghaesembilla Gaertn. | Kath marmuri (O) | Phyllanthaceae | NN–264 | Tree | Apr–Oct |

| 23 | Azadirachta indica A.Juss. | Nimba (O) | Meliaceae | NN–261 | Tree | Feb–Jul |

| 24 | Bacopa monnieri (L.) Pennell. | Brahmi (O) | Plantaginaceae | NN–211 | Herb | Apr–Dec |

| 25 | Basella alba L. | Poi (O) | Basellaceae | NN–284 | Climber | Dec–Feb |

| 26 | Bauhinia purpurea L. | Raajbiji (O) | Fabaceae | NN–239 | Tree | Sep–Mar |

| 27 | Bauhinia variegata (L.) Benth. | Kanchano (O) | Fabaceae | NN–322 | Tree | Feb–May |

| 28 | Benincasa hispida (Thunb.) Cogn. | Panikakharu (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–254 | Climber | Oct–Jan |

| 29 | Boerhavia diffusa L. nom. cons. | Puruni (O) | Nyctaginaceae | NN–347 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 30 | Brassica napus L. | Sorisa (O) | Brassicaceae | NN–372 | Herb | Sep–Feb |

| 31 | Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis L. | Phulkobi (O) | Brassicaceae | NN–356 | Herb | Nov–Mar |

| 32 | Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata L. | Bandha kobi (O) | Brassicaceae | NN–374 | Herb | Dec–Feb |

| 33 | Brassica oleracea L. var. gongylodes L. | Olkobi (O) | Brassicaceae | NN–368 | Herb | Dec–Feb |

| 34 | Capsicum annuum L. | Lanka (O) | Solanaceae | NN–221 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 35 | Cayratia auriculata (Roxb.) Gamble | Nadara dunka (O) | Vitaceae | NN–335 | Climber | Jul–Dec |

| 36 | Celosia argentea L. | Nahanga Saga (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–288 | Herb | Aug–Jan |

| 37 | Centella asiatica (L.) Urban | Thalkuri (O) | Apiaceae | NN–270 | Herb | May–Nov |

| 38 | Chenopodium album L. | Bathua Saga (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–237 | Herb | Nov –Apr |

| 39 | Cheilocostus speciosus (J.Konig) C. Specht | Gaigobra (O) | Costaceae | NN–392 | Herb | July–Dec |

| 40 | Cicer arietinum L. | Chana (O) | Fabaceae | NN–378 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 41 | Cissampelos pareira L. | Akanabindi (O) | Menispermaceae | NN–316 | Climber | Jun–Jan |

| 42 | Clerodendrum infortunatum L. | Ghetu (B) | Lamiaceae | NN–383 | Shrub | Jan–Jul |

| 43 | Cleome viscosa L. | Anasorisha (O) | Cleomaceae | NN–202 | Herb | May–Oct |

| 44 | Cleome rutidosperma DC | Anasorisha (O) | Cleomaceae | NN–215 | Herb | Dec–Feb |

| 45 | Coccinia grandis (L.) Voigt | Kundri (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–269 | Climber | Jun–Sep |

| 46 | Cocculus hirsutus (L.) Diels | Musakani (O) | Menispermaceae | NN–331 | Climber | Apr–May |

| 47 | Coleus barbatus (Andrews) Benth. ex G.Don | Rukunahata pochha (O) | Lamiaceae | NN–283 | Herb | Oct–Dec |

| 48 | Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott. | Saru (O) | Araceae | NN–394 | Herb | Jun–Nov |

| 49 | Commelina benghalensis L. | Kaniseera (O) | Commelinaceae | NN–223 | Herb | Jul–Jan |

| 50 | Commelina erecta L. | Konisir (O) | Commelinaceae | NN–253 | Herb | Aug–Dec |

| 51 | Corchorus aestuans L. | Bana nalita (O) | Malvaceae | NN–245 | Herb | Jul–Dec |

| 52 | Corchorus capsularis L. | Jhutto/Nalita (O) | Malvaceae | NN–302 | Herb | May–Nov |

| 53 | Corchorus olitorius L. | Madhura nalita (O) | Malvaceae | NN–303 | Herb | Jul–Nov |

| 54 | Cordia dichotoma G. Forst. | Sheluka (B) | Boraginaceae | NN–361 | Tree | Mar–Sep |

| 55 | Coriandrum sativum L. | Dhaniya (O) | Apiaceae | NN–291 | Herb | Nov–Mar |

| 56 | Cucumis sativus L. | Kakudi (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–255 | Climber | Sep–Nov |

| 57 | Cucurbita maxima Duchesne | Boitalu (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–273 | Climber | Mar–Aug |

| 58 | Cucurbita pepo L. | Kakharu (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–258 | Climber | Jul–Oct |

| 59 | Cyanotis axillaris (L.) D.Don ex Sweet | Kanasari (O) | Commelinaceae | NN–262 | Herb | Jul–Jan |

| 60 | Cycas orixensis (Haines) Singh & Khuraijam | Bheru (O) | Cycadaceae | NN–349 | Tree | May–Oct |

| 61 | Dicliptera bupleuroides Nees. | Khaparakatia (O) | Acanthaceae | NN–262 | Herb | Sep–Feb |

| 62 | Diplazium esculentum (Retz) Sw. | Dheki Saag (B) | Athyriaceae | NN–327 | Pteridophyte | Jan–Dec |

| 63 | Eclipta prostrata (L.) L. | Bhrungaraj (O) | Asteraceae | NN–272 | Herb | Aug–Apr |

| 64 | Enydra fluctuans Lour. | Hidimicha Sago (O) | Asteraceae | NN–311 | Herb | Dec–Feb |

| 65 | Eryngium foetidum L. | Jangli dhania (O) | Apiaceae | NN–340 | Herb | Apr–Aug |

| 66 | Erythrina variegata L. | Paladhua (O) | Fabaceae | NN–333 | Tree | Mar–Jul |

| 67 | Euphorbia hirta L. | Chita–kutei (O) | Euphorbiaceae | NN–241 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 68 | Ficus religiosa L. | Aswatta (O) | Moraceae | NN–385 | Tree | Jun–Oct |

| 69 | Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Pan mohari (O) | Apiaceae | NN–369 | Herb | Oct–Mar |

| 70 | Glinus oppositifolius (L.) Aug. DC. | Pitagama (O) | Molluginaceae | NN–293 | Herb | Mar–Oct |

| 71 | Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | Kaunria Saga (O) | Malvaceae | NN–355 | Herb | Jul–Feb |

| 72 | Hygrophila auriculata Schumach. | Koelekha (O) | Acanthaceae | NN–308 | Herb | Oct–Feb |

| 73 | Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. | Kalama Saga (O) | Convolvulaceae | NN–260 | Herb | Nov–Mar |

| 74 | Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. | Kandumulo (O) | Convolvulaceae | NN–344 | Herb | Dec–Jan |

| 75 | Ipomoea sepiaria Koenig ex Roxb. | Mushakani (O) | Convolvulaceae | NN–370 | Climber | Oct–Apr |

| 76 | Justicia adhatoda L. | Basango (O) | Acanthaceae | NN–359 | Shrub | Jun–Feb |

| 77 | Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet | Simbo (O) | Fabaceae | NN–310 | Climber | Oct–Feb |

| 78 | Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. | Lau (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–377 | Climber | Jul–Feb |

| 79 | Leucas aspera (Willd.) Link | Gaiso (O) | Lamiaceae | NN–299 | Herb | Jul–Jan |

| 80 | Leucas cephalotes (Roth) Spreng. | Goyoso (O) | Lamiaceae | NN–292 | Herb | Aug–Dec |

| 81 | Luffa acutangula (L.) Roxb. | Janni (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–279 | Climber | Aug–Nov |

| 82 | Luffa aegyptica Mill. | Tadari/Pitta Torai (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–266 | Climber | Aug–Nov |

| 83 | Marsilea minuta L. | Sunsunia Saga (O) | Marsileaceae | NN–286 | Pteridophyte | Nov–Mar |

| 84 | Marsilea quadrifolia L. | Sunsunia saga (O) | Marsileaceae | NN–325 | Pteridophyte | Nov–Feb |

| 85 | Mentha spicata L. | Pudina (O) | Lamiaceae | NN–320 | Herb | Jul–Sep |

| 86 | Merremia quinquefolia (L.) Hallier f. | Chadhei saga (O) | Convolvulaceae | NN–351 | Climber | Apr–Sep |

| 87 | Mollugo pentaphylla L. | Pita saga (O) | Molluginaceae | NN–324 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 88 | Momordica charantia L. | Kalara (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–265 | Climber | Jun–Feb |

| 89 | Momordica dioica Roxb. ex. Willd | Kankada (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–280 | Climber | Aug–Nov |

| 90 | Moringa oleifera Lam. | Sajana (O) | Moringaceae | NN–229 | Tree | Jan–Jun |

| 91 | Murraya koenigii (L.) Spreng. | Bhursunga (O) | Rutaceae | NN–375 | Tree | Feb–Sep |

| 92 | Nyctanthes arbor–tristis L. | Gangaseoli (O) | Oleaceae | NN–399 | Tree | Sep–Jan |

| 93 | Olax scandens Roxb. | Bhadbhadia (O) | Olacaceae | NN–387 | Shrub | Mar–Dec |

| 94 | Oxalis corniculata L. | Ambiliti (O) | Oxalidaceae | NN–315 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 95 | Paederia foetida L. | Prasaruni (O) | Rubiaceae | NN–338 | Climber | Aug–Oct |

| 96 | Pisum sativum L. | Matar (O) | Fabaceae | NN–352 | Herb | May–Oct |

| 97 | Polygonum plebeium R.Br. | Muthi saga (O) | Polygonaceae | NN–294 | Herb | Feb–Jun |

| 98 | Portulaca quadrifida L. | Balbalua (O) | Portulacaceae | NN–309 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 99 | Portulaca oleracea L. | Badabalbalua (O) | Portulacaceae | NN–342 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 100 | Pontederia hastata L. | Konsida (O) | Pontederiaceae | NN–391 | Hydrophyte | Apr–Sep |

| 101 | Raphanus sativus L. | Mula saga (O) | Brassicaceae | NN–300 | Herb | Jan–Feb |

| 102 | Rungia pectinata (L.) Nees | Sankh Sago (O) | Acanthaceae | NN–332 | Herb | Nov–Feb |

| 103 | Senna sophera (L.) Roxb | Ghodachakunda (O) | Fabaceae | NN–217 | Shrub | Aug–Feb |

| 104 | Senna tora (L.) Roxb. | Chakunda (O) | Fabaceae | NN–262 | Herb | Sep–Dec |

| 105 | Senna occidentalis (L.) Link | Kola chakunda (O) | Fabaceae | NN–329 | Herb | Sep–Feb |

| 106 | Sesbania grandiflora (L.) Poiret | Agasthi (O) | Fabaceae | NN–213 | Tree | Nov–May |

| 107 | Sesbania sesban (L.) Merr. | Jayanti (O) | Fabaceae | NN–218 | Shrub | Oct–Jan |

| 108 | Solanum lycopersicum L. | Bilati baigan (O) | Solanaceae | NN–337 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 109 | Solanum melongena L. | Baigana (O) | Solanaceae | NN–341 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 110 | Solanum tuberosum L. | Alu (O) | Solanaceae | NN–268 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 111 | Spermacoce articularis L.f. | Solaganthi (O) | Rubiaceae | NN–360 | Herb | July–Dec |

| 112 | Spinacea oleracea L. | Palanga (O) | Amaranthaceae | NN–257 | Herb | Nov–Feb |

| 113 | Spondias pinnata (L.f.) Kurz. | Ambada (O) | Anacardiaceae | NN–210 | Tree | Feb–Mar |

| 114 | Streblus taxoides (Roth) Kurz. | Phutkuli (O) | Moraceae | NN–366 | Tree | Mar–Jun |

| 115 | Talinum fruticosum (L.) Juss. | Jangli Poi (O) | Talinaceae | NN–290 | Herb | Oct–Jan |

| 116 | Tamarindus indica L. | Tentuli (O) | Fabaceae | NN–216 | Tree | Jan–Jun |

| 117 | Telosma pallida (Roxb.) W.G. Craib | Tokeikundei (O) | Apocynaceae | NN–307 | Climber | May–Jan |

| 118 | Tinospora cordifolia (Thunb.) Miers | Guluchi (O) | Menispermaceae | NN–365 | Climber | Aug–May |

| 119 | Trichosanthes cucumerina L. | Chichendara (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–400 | Climber | May –Aug |

| 120 | Trichosanthes dioica Roxb. | Potala (O) | Cucurbitaceae | NN–252 | Climber | Apr– Sep |

| 121 | Trianthema protulacastrum L. | Khapara Sago (O) | Aizoaceae | NN–281 | Herb | Jul–Dec |

| 122 | Trigonella corniculata (L.) L. | Piring Saga (O) | Fabaceae | NN–393 | Herb | Nov–Mar |

| 123 | Trigonella foenum–graecum L. | Methi Saaga (O) | Fabaceae | NN–397 | Herb | Dec–Mar |

| 124 | Typhonium trilobatum (L.) Schott | Ghet Kachhu (B) | Araceae | NN–350 | Herb | Jan–Dec |

| 125 | Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. | Jhudango (O) | Fabaceae | NN–357 | Climber | Jul–Oct |

| 126 | Zanthoxylum asiaticum (L.) Appelhans, Groppo & J.Wen | Tundpora (O) | Rutaceae | NN–345 | Climber | Aug–Apr |

| Figure 2: Habit-wise distribution (in %) of leafy vegetables in Balasore district. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 3: Family-wise distribution of leafy vegetables in Balasore district. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 4: Genus-wise distribution of leafy vegetables in Balasore district. [Click here to view] |

It is worth noting that 25 ethnomedicinally potent leafy vegetables belonging to 16 families under 25 genera were documented in the study area, which was used to treat gastrointestinal disorders [Table 2]. The most cited ethnomedicinal leafy vegetables are Oxalis corniculata L., Eryngium foetidum L., A. aspera L., A. lanata (L.) Juss. ex Schult., Momordica charantia L., and Murraya koenigii (L) Spreng. Among the most frequently cited indigenous medicinal leafy vegetables, four species displayed greater than a 75% Fl [Table 3]. O. corniculata L., with a Fl of 93.83%, was observed to be the most recommended species against diarrhea. Interestingly, the observations of the present study on O. corniculata in the treatment of diarrhea are supported by the studies of several researchers [26-28]. Orally, 10 ml of leaf juice of this plant mixed with a little sugar candy powder is administered twice a day for 2 days to treat diarrhea. Apart from their culinary uses, they have the potential to meet the primary health-care needs of the tribal and rural people, thereby preserving their endangered ethnomedicinal knowledge.

Table 2: Ethnomedicinal uses of leafy vegetables against gastrointestinal disorders.

| Botanical name and family | Vernacular name | Tribe | Parts used and treatment mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Achyranthes aspera L. [Amaranthaceae] | Buridataram | Santal | Leaves: 1–2 teaspoonful leaf juice is orally administered 3 times a day for 7 days on an empty stomach for curing peptic ulcer |

| Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. ex Schult. [Amaranthaceae] | Chindi | Oraon | Leaves: Leaf paste along with boiled rice is grinded and made into cake and consumed for treating dysentery |

| Antidesma acidum Retz. [Phyllanthaceae] | Matha arak | Santal | Leaves: Dried leaf powder along with water is given for curing dysentery |

| Basella alba L. [Basellaceae] | Purai | Santal | Leaves: ¼ th of the leaf along with two black pepper is grinded and is taken three times a day for treating diarrhoea |

| Cayratia auriculata (Roxb.) Gamble [Vitaceae] | Nadara dunka | Bhumija | Leaves: Dried leaves made into powder and taken for curing dysentery |

| Cicer arietinum L. [Fabaceae] | But arak | Santal | Seeds: 50 g of seeds soaked overnight in water is prescribed raw for treating constipation |

| Cocculus hirsutus (L.) Diels [Menispermaceae] | Musakani | Santal | Leaves: For treating stomach aches, leaf juice along with fresh curd is given twice a day for 3 days |

| Coleus barbatus (Andrews) Benth. ex G.Don [Lamiaceae] | Ban juani | Bhumija | Leaves: 10 ml leaf juice along with a pinch of rock salt is given once in every one hour for curing diarrhea |

| Cucurbita pepo L. [Cucurbitaceae] | Kahanda arak | Santal | Seeds: For expelling intestinal worms, a paste prepared by mixing 25 g seed kernel along with a little water and jaggery is given with 4 teaspoonful warm milk in the morning after breakfast |

| Eclipta prostrata (L.) L. [Asteraceae] | Kala kesadura | Oraon | Leaves: 10 ml of leaf juice added with 20 ml sheep’s milk is taken 2 times a day for treating dysentery |

| Eryngium foetidum L. [Apiaceae] | Jangli dhania | Bhumija | Leaves: To stop vomiting caused due to indigestion, 10 ml leaf decoction is consumed 2 times a day on an empty stomach |

| Erythrina variegata L. [Fabaceae] | Paladhua | Oraon | Leaves: To expel intestinal worms in children, 1–2 teaspoonfuls of leaf juice are orally administered once a day for 3–4 days |

| Ficus religiosa L. [Moraceae] | Hesak arak | Santal | Bark: Ash obtained from burnt bark is blended with water and given 2–4 teaspoonful in every 1 h for curing vomiting |

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. [Apiaceae] | Pan mohari | Oraon | Seeds: Mixture of 10 g seeds and 50 g sugar is boiled in100 ml water and the syrup (5 ml) obtained is given to children 3 times in a day for curing colic and stomach pain caused by gas |

| Hygrophila auriculata Schumach. [Acanthaceae] | Koelekha | Bhumija | Leaves: Equal amount of leaf juice and lemon juice is given once a day for 3 days against worm infestation |

| Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet [Fabaceae] | Simbo | Bhumija | Fruit: For relieving constipation, stir–fried fruit is consumed |

| Mentha spicata L. [Lamiaceae] | Pudina sakaam | Santal | Leaves: For the cure of diarrhoea, a mixture of leaf juice (10 ml), sunthi powder (5 g dried ginger) and a little salt is given |

| Momordica charantia L. [Cucurbitaceae] | Kaalra sakaam | Santal | Leaves: For complete deworming in children, 20 ml of leaf juice is prescribed in the early morning on an empty stomach for 4–5 days |

| Murraya koenigii (L.) Spreng. [Rutaceae] | Kadhi patta | Bhumija | Leaves: About ½ cup of fresh leaf juice is given in the early morning on an empty stomach to treat hyperacidity |

| Oxalis corniculata L. [Oxalidaceae] | Chomorakoi arak | Santal | Leaves: 10 ml leaf juice along with a little sugar candy powder is given to children twice a day for 2 days for treating diarrhoea |

| Portulaca oleracea L. [Portulacaceae] | Bek saga | Oraon | Leaves: Leaves are boiled, stir–fried and eaten to get rid of intestinal worms |

| Raphanus sativus L. [Brassicaceae] | Mula arak | Santal | Fruit: 20 ml fruit juice added with 10 g sugar candy powder is orally administered twice (morning and evening) on an empty stomach to treat hyperacidity |

| Spinacea oleracea L. [Amaranthaceae] | Palanga | Santal | Leaves: 50 mL of leaf juice and 50 mL of tomato juice are boiled together with a pinch of black salt and black pepper powder and taken orally to treat indigestion and to regain taste |

| Tamarindus indica L. [Fabaceae] | Jojo | Santal | Leaves: For curing vomiting, leaves are boiled and the resulting filtered water is consumed |

| Trichosanthes dioica Roxb. [Cucurbitaceae] | Potala | Oraon | Leaves: To cure diarrhoea, leaf decoction mixed with black pepper powder is orally administered |

Table 3: Fidelity level (Fl%) of most cited leafy vegetables against gastrointestinal disorders.

| Species | Ailments | NP | N | Fl% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxalis corniculata L. | Diarrhoea | 137 | 146 | 93.83 |

| Eryngium foetidum L. | Vomiting | 107 | 139 | 76.97 |

| Achyranthes aspera L. | Peptic ulcer | 62 | 81 | 76.54 |

| Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. ex Schult. | Dysentery | 84 | 111 | 75.67 |

| Momordica charantia L. | Deworming | 128 | 197 | 64.97 |

| Murraya koenigii (L.) Spreng. | Hyperacidity | 112 | 177 | 63.27 |

To determine tribal general agreement in the use of the recorded ethnomedicinal plants, the Fic values of total gastrointestinal disorders was categorized into nine groups. The average Fic value obtained for all gastrointestinal disorders categories was 0.982, indicating that most tribals in the Balasore district were well aware of ethnomedicinal plant knowledge. The gastrointestinal disorder category-”peptic ulcer” attained the highest Fic value of 1 [Table 4]. A Fic value of 1 indicated that a large number of respondents used fewer plant species to treat peptic ulcers, thereby indicating that specific plant remedies against peptic ulcers were well practiced among informants in the study area. A. aspera L. is used for treating peptic ulcers by the tribals of Balasore district. To treat a peptic ulcer, 1–2 teaspoons of its leaf juice are taken orally 3 times a day on an empty stomach for 7 days. Furthermore, a good number of studies have supported the gastroprotective effects of A. aspera against peptic ulcers [29-31].

Table 4: Factor of informant consensus (Fic) value of each disease category.

| Diseases categories | Number of taxa | Used report | Fic values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoea | 5 | 163 | 0.975 |

| Deworming | 5 | 141 | 0.971 |

| Dysentery | 4 | 97 | 0.968 |

| Vomiting | 3 | 144 | 0.986 |

| Indigestion | 3 | 87 | 0.976 |

| Constipation | 2 | 108 | 0.99 |

| Hyperacidity | 2 | 121 | 0.991 |

| Peptic ulcer | 1 | 62 | 1 |

| Colic and | 2 | 93 | 0.989 |

| Stomach ache |

The results of the present investigation revealed that many unexplored or lesser-known leafy vegetables are still consumed by the tribal and indigenous people, which need immediate documentation and preservation. Several leafy vegetables were used against gastrointestinal complaints, which indicated that they boost our gut health and provide a healthy gut environment. In addition, they are loaded with nutrients and antioxidants that help improve our immunity, thereby protecting us against different diseases. Further, ethnomedicinal leafy vegetables with high FL and Fic values that have not been investigated yet can be screened for phytochemical, nutritional, antioxidant, and pharmacological analysis to discover novel drugs to treat various diseases. However, due to a lack of awareness among people about their beneficial effects, they are underutilized. Therefore, it is recommended that immediate necessary measures should be taken for its exploration, documentation, and conservation for the future sustainable utilization.

4. CONCLUSION

The present study reveals that indigenous leafy vegetables can play a prominent role in addressing developing countries’ food scarcity and malnutrition issues. Wild edible plants ensure food security and household income for tribal and rural communities. Documentation and exploration of indigenous leafy vegetables would open up new horizons for popularizing their wider consumption by the indigenous people in their diet, thereby promoting good health. Further research on a greater scale is required to reveal their potential as the future medicines. However, there is an urgent need for restoration and perpetuation of ethnomedicinal uses of indigenous leafy vegetables that face severe genetic loss. Mainstreaming the use of nutrient-rich underutilized leafy vegetables fulfills not only dietary requirements but also meets new market demands. Furthermore, an integrated conservation approach will be an effective measure for the sustainable utilization of undervalued leafy vegetables. Joint forest management, participatory rural appraisal, organic farming, in situ conservation strategies, bioprospection, biofortification, and commercialization are essential for effectively utilizing underutilized leafy vegetables.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are thankful to the administration and management of Centurion University of Technology and Management, Odisha, India, for their support during the investigation.

6. AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

KBS and NN conceived the idea. NN performed the experiments. KBS and NN analyzed the information. Both authors have made significant contributions in drafting the manuscript.

7. FUNDING

There is no funding to report.

8. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

9. ETHICAL APPROVALS

This study does not involve experiments on animal and human subjects.

10. DATA AVAILABILITY

All data generated and analyzed are included within this research article.

11. PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

REFERENCES

1. Sheela K, Nath KG, Vijayalakshmi D, Yankanchi GM, Patil RB. Proximate composition of underutilized green leafy vegetables in Southern Karnataka. J Hum Ecol 2004;15:227-9. [CrossRef]

2. Jana JC. Use of traditional and underutilized leafy vegetables of Sub-Himalayan terai region of West Bengal. Acta Hortic 2007;752:571-5. [CrossRef]

3. Sreenivasa RJ. Nutrition science in India:Green leafy vegetables:A potent food source to alleviate micronutrient deficiencies. Int Res J Basic Appl Sci 2017;2:7-13.

4. Keshari AN, Gupta RK, Watal G. Hypoglycemic effects of

5. Yamamura S, Ozawa K, Ohtani K, Kasai R, Yamasaki K. Antihistaminic flavones and aliphatic glycosides from

6. Rajeshkumar NV, Joy KL, Kuttan G, Ramsewak RS, Nair MG, Kuttan R. Anti-tumour and anticarcinogenic activity of

7. Moller SM, Jacques PF, Blumberg JB. The potential role of dietary xanthophylls in cataract and age related macular degeneration. Indian J Am Coll Nutr 2000;19:522-7. [CrossRef]

8. Noor N, Satapathy KB. Indigenous leafy vegetables:A super-food and a potent drug for future generation. Int J Bot Stud 2020;5:146-53.

9. Hanson BT, Dimitri Kits K, Löffler J, Burrichter AG, Fiedler A, Denger K,

10. Speciale G, Jin Y, Davies GJ, Williams SJ, Goddard-Borger ED. YihQ is a sulfoquino-vosidase that cleaves sulfoquinovosyl diacylglyceride sulfolipids. Nat Chem Biol 2016;12:215-7. [CrossRef]

11. Panda T. Traditional knowledge on wild edible plants as livelihood food in Odisha, India. J Biol Earth Sci 2014;4:144-59.

12. Padhan B, Panda D. Wild edible plant diversity and its ethno-medicinal use by indigenous tribes of Koraput, Odisha, India. Res J Agric For Sci 2015;3:1-10.

13. Samal D, Rout NC, Biswal AK. Contribution of wild edible plants to the food security, dietary diversity and livelihood of tribal people of Keonjhar district, Odisha. Plant Sci Res 2019;41:20-33.

14. Mallick SN, Sahoo T, Naik SK, Panda PC. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible food plants used by the Tribals and rural populations of Odisha, India for food and livelihood security. Plant Arch2020;20:661-9.

15. Mallick SN, Naik SK, Panda PC. Diversity of wild edible food plants and their contribution to livelihood of tribal people in Nabarangpur district, Odisha. Plant Sci Res 2017;39:64-75.

16. Behera KK, Mishra NM, Dhal NK, Rout NC. Wild edible plants of Mayurbhanj district, Orissa, India. J Econ Taxon Bot 2008;32

17. PandaT, Mishra N, Pradhan BK, Mohanty RB. Diversity of leafy vegetables and its significance to rural households of Bhadrak district, Odisha, India. Sci Agric 2015;11:114-23. [CrossRef]

18. Mohanty SP, Rautaray KT. Survey of leafy vegetables/saka/saag used in and around Gandhamardan hills, Nrusinghnath, Bargarh district, Odisha. Int J Sci Res 2020;

19. Haines HH. The Botany of Bihar and Orissa, 6 Parts. London:Adlard and Son Ltd.;1921-1925.

20. Saxena HO, Brahmam M. The Flora of Orissa. Vol. 1-4. Bhubaneswar (Orissa):Regional Research Laboratory and Forest Development Corporation of Orissa;1994-1996.

21. Mooney HF. Supplement to the Botany of Bihar and Orissa. Ranchi:Catholic Press;1950.

22. Jain SK, Rao RR. A Handbook for field and herbarium methods. New Delhi:Today and Tomorrow Publishers;1967.

23. Trotter RT, Logan MH. Informant consensus:A new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In:Etkin NL, editor. Plants in Indigenous Medicine and Diet, Behavioural Approaches. Bredfort Hills. New York:Redgrave Publishing Company;1986. 91-112. [CrossRef]

24. Heinrich M, Ankli A, Frei B, Weimann C, Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico:Healers'onsensus and cultural importance. Soc Sci Med1998;47:1859-71. [CrossRef]

25. Friedman J, Yaniv Z, Dafni A, Palewitch D. A preliminary classification of healing potential plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethno pharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev desert. J Ethnopharmacol 1986;16:275-87. [CrossRef]

26. Watcho P, Nkouathio E, Nguelefack TB, Wansi SL, Kamany A. Antidiarrhoeal activity of aqueous and methanolic extracts of

27. Mukherjee S, Koley H, Barman S, Mitra S, Datta S, Ghosh S,

28. Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian Medicinal Plants. 3rd ed., Vol. 1. New Delhi:MS Periodical Experts;1975. 437.

29. Das AK, Bigoniya P, Verma NK, Rana AC. Gastroprotective effect of

30. Mishra V, Mishra SK, Onasanwo SA, Palit G, Mahdi AA, Agarwal SK,

31. Bigoniya P. Effect of methanolic extract of