1. INTRODUCTION

Underground modified crops are plants with starchy roots; these are mostly used by humans as food [1]. In developing countries, these are important sources of food both for humans as well as animals. According to Scott et al., these rooted crops generate more carbohydrate per hectare per day and yield more energy than any other food crops, even under adverse growing conditions [2]. Dioscorea alata L. (yam), a member of the family Dioscoreaceae, is a twining climber characterized by its modified tuberous roots. The plant is dioecious, bearing male and female reproductive structures on separate plants, typically on axillary spikes. Male inflorescences are long, slender, and highly branched, whereas female spikes are comparatively shorter and less branched. Male flowers have six tepals and six stamens, which are positioned opposite the tepals. The female flowers also possess six tepals and contain a trilocular, inferior ovary topped with three bifid stigmas. The fruit develops as a capsule [3]. D. alata is ranked as the third most widely consumed tuber crop globally, following cassava and sweet potato [4]. At present, yam cultivation is reported in 61 countries, with African nations contributing approximately 98.20% of global production [5]. In 2021, total yam output reached 75 million tonnes, cultivated across more than 8.8 million ha of land [6]. In India, yam production stands at 8.10 lakh tonnes, covering an area of 30,000 ha. In India, the major yam-producing states include Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh [5]. In Odisha, D. alata is widely consumed and holds cultural and dietary significance across various regions of the state [7]. It acts as one of the major food and medicinal sources for rural and tribal people of Odisha [8]. Its tubers are rich in carbohydrates, protein, vitamins, and other nutrients [7,9,10]. After harvest, yams are usually stored at room temperature for a long time, but it is difficult to control its germination and post-harvest decay during storage [11]. During post-harvest storage, high temperature usually increases the severity of decay [12,13], and in Odisha, these crops face huge microbial decay due to its warm climatic conditions, which cause serious problems and sustain heavy losses. Okigbo and Ikediugwu in 2000 reported that around 20–39.5% storage decay of yams occurs because of microbes, whereas it was around 40% by the estimation of Bonire [8,14]. Among the microbes, fungi are mainly causal agents of post-harvest rotting of yams [15,16]. In general, farmers use different types of chemical fungicides to control the fungal decay of yam tubers for long-term post-harvest storage [17-21]. Despite knowing their negative impacts on health and the environment, these chemicals are still predominantly used by local farmers and agro-wholesalers in most of the developing countries [22]. However, now, the studies on the potential use of plants and their products have opened a new slant to control the microbe-based plant diseases. These are safe, non-toxic, eco-friendly, and sustainable ways to control the plant pathogens [23].

In view of this background, the objectives of this study were to isolate fungal pathogens associated with storage rots of yams, its morphological and molecular identification, followed by the study of their control using medicinal plants.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODOLOGY

2.1. Collection of Samples

A total of 280 yam tubers showing clear signs of rot – such as discoloration, mycelial growth, tissue decay, foul odour, and other indicative symptoms – were collected in three phases from various regions across Odisha, India. The affected tubers were individually placed in sterile polythene bags and transported to the Microbiology Laboratory at the Department of Botany, Utkal University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, for further phytopathological analysis.

2.2. Isolation of Fungus

The collected tubers were initially washed with tap water and surface sterilized using 0.1% mercuric chloride solution for 2–3 min to eliminate surface contaminants. Of the 280 tubers collected, 58 exhibiting severe infections were selected for further study. Their symptomatology and morphological features were recorded. Each tuber was cut into small sections (5 × 5 mm) using a sterile knife, starting from healthy tissue and moving toward infected areas. Tissue fragments from the infected regions were plated onto potato dextrose agar (PDA, Hi-Media) and incubated at room temperature for 24–35 h. Representative fungal colonies were purified by subculturing onto fresh PDA plates. Pure cultures were maintained on PDA slants for subsequent cultivation. The frequency of fungal incidence was calculated using the formula: Frequency of incidence (%) = (X/Y) × 100, where X = number of tubers showing fungal growth, and Y = total number of tubers examined. All procedures were replicated 3 times, and the results were recorded for statistical accuracy.

2.3. Identification of Fungus

The isolated fungus was cultured on PDA plates for identification. Morphological characteristics were observed using the slide culture technique [24]. For molecular identification, genomic DNA was extracted from the fungal isolate [25], followed by amplification of the 26S rRNA gene with universal primers DF (5’-ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC-3’) and DR (5’-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG-3’). The amplified product was sequenced at Xcelris Genomics, India. The raw sequence data were analyzed using BioEdit software (v7.0.5.3), and the identity of the isolate was determined by BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) against the NCBI nucleotide database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the MUSCLE algorithm [26]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the UPGMA distance algorithm in Mega software v5.1, and its topology was validated through bootstrap analysis of the MUSCLE dataset with 500 resamplings. The final sequence was submitted to NCBI GeneBank for the assignment of an accession number.

2.4. Pathogenicity Test

A pathogenicity test was conducted to evaluate the virulence of the fungal isolate. A total of 160 fresh, healthy yam tubers were collected, washed, and surface sterilized using 0.1% mercuric chloride for 2–3 min. Cylindrical cores (5 mm) were removed from each tuber using a sterile cork borer. Each tuber received one inoculation site, into which a 4 mm PDA disc containing a 7-day-old fungal culture was inserted. The wounds were sealed with sterile Vaseline and wrapped in moist sterile cotton. Control tubers received PDA discs without fungal inoculum. All tubers were individually packed in sterile polythene bags and incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 10 days. Post-incubation, tubers were assessed for infection symptoms – weight loss, lesion diameter, mycelial growth, and odour [27]. For statistical robustness, three replicates of 50 tubers each (total = 150) were tested, along with 10 healthy tubers maintained as uninoculated controls. The presence of the pathogen was reconfirmed through morphological examination and microscopic re-isolation. Observed symptoms and the extent of decay were compared with those found in naturally infected tubers. The incidence of rot was calculated using the same formula: Incidence (%) = W/Z×100, where W represents the number of tubers showing rot, and Z represents the total number of inoculated tubers. Each replicate was analyzed independently. For tubers infected through artificial inoculation, pathogenicity (degree of rotting) was assessed by comparing the lesion diameter with the total surface area of each tuber and expressed as a percentage.

2.5. Nutritional Study

A comparative nutritional study was conducted to evaluate the effect of different solid nutrient media on the growth of the isolated fungus. The solid media tested included Czapek dox agar (CDA), Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA), and PDA [22]. A piece of well-grown mature mycelium was placed at the center of the test petriplates carrying nutrient media and kept for 7 days at 28 ± 2°C inside the incubator [27].

2.6. Collection and Identification of Plant Material

In this investigation, the leaves of 16 medicinal plants were studied: Ageratum conyzoides, Abutilon indicum, Artocarpus heterophyllus, Alstonia scholaris, Averrhoa carambola, Centella asiatica, Cassia fistula, Dillenia indica, Eucalyptus globulus, Haldina cordifolia, Justicia adhatoda, Lawsonia inermis, Murraya paniculata, Pithecellobium dulce, Pongamia pinnata, and Tamarindus indica. These plants were collected from the Chandaka Reserve Forest area near Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. The identification of voucher plant specimens was performed using available literature [28]. The specimens were preserved as herbarium samples and deposited in the Post-Graduate Department of Botany, Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar, Odisha.

The collected leaves were processed in bulk. They were washed under running tap water, dried in the shade, and ground into a coarse powder. The powdered samples were then successively extracted with petroleum ether and methanol using a Soxhlet apparatus [29]. The extracts were concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator and stored in desiccators for further use.

2.7. In vitro Control of Isolated Fungus

The in vitro antifungal activity of the isolated fungus was evaluated using both plant-based extracts and synthetic fungicides. For this purpose, petroleum ether and methanolic leaf extracts of the sixteen previously mentioned medicinal plants were tested. In parallel, the efficacy of synthetic fungicides Dhanustin, Mancozeb, Blitox-50, and Indofil was also assessed. Plant extract samples were prepared by dissolving three concentrations (20, 10, and 5 mg/mL) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). In contrast, synthetic fungicide solutions were prepared using sterile distilled water at a concentration of 0.05 mg/mL. The antifungal activity was determined using the poisoned food technique, following the method described by Satish et al. with slight modifications [30]. For treatment preparation, 1 mL of each diluted sample was added to 19 mL of molten PDA, and the mixture was poured into sterile petri plates (20 mL/plate) and allowed to solidify. PDA medium containing 1 mL of DMSO without any test sample served as the control. A 0.5 cm disc of the 7-day-old fungal culture was placed at the center of each plate, and the plates were incubated at 27°C for 5 days. Each treatment, including controls, was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. The antifungal efficacy of each plant extract and fungicide was assessed by measuring the radial growth of fungal colonies (in cm). The percentage inhibition of fungal growth (zone of restriction) was calculated using the following formula [31]:

% Inhibition = [(A–B)/A] × 100, where:

A = average increase in mycelial growth in the control,

B = average increase in mycelial growth in the treatment (plant extracts).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Identification and Characterization of Junghuhnia sp. AK15

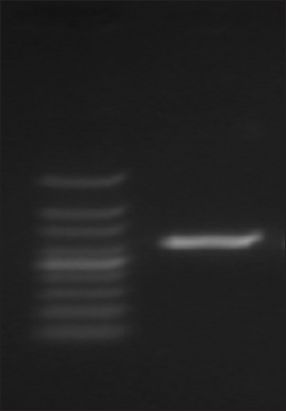

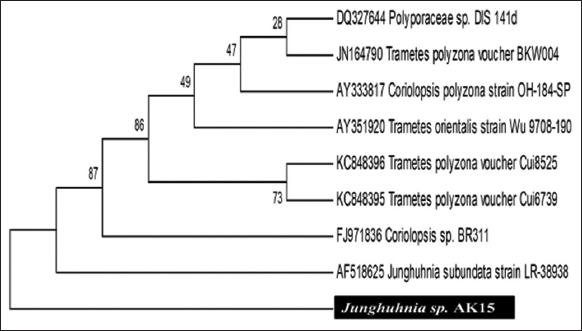

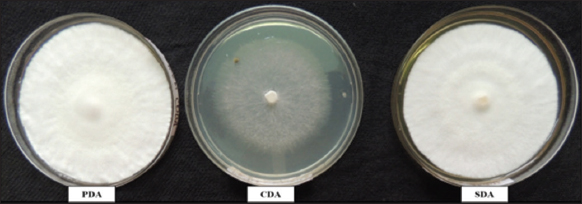

The fungus Junghuhnia sp. AK15 (GenBank accession number: KT946990; NCBI: txid1792223) was identified as the causal agent of post-harvest rot in yam tubers. In culture media, it exhibits a characteristic milky-white, velvety mycelial growth. Upon maturation, the culture produces numerous colourless spores, and the aging mycelium develops abundant pale-yellow, small oil globules [Figure 4a]. Microscopic observations revealed dimitic hyphal systems composed of clamped, sparingly branched, cyanophilous skeletal hyphae. The fungus also forms oval, smooth, colourless, and thick-walled basidia [Figure 4b]. Molecular identification based on sequence analysis showed 99% similarity with Junghuhnia subundata strain LR-38938 (GenBank accession number: AF518625) [Figure 3]. The detailed nucleotide sequence of Junghuhnia strain AK15 is presented in Figures 1 and 2. The taxonomic lineage of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 is as follows: Eukaryota; Fungi; Dikarya; Basidiomycota; Agaricomycotina; Agaricomycetes; Polyporales; Steccherinaceae; Junghuhnia; and strain AK15.

| Figure 1: S Ribosomal RNA nucleotide sequence of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 (< 1 >656). [Click here to view] |

| Figure 2: Visualization of the 26S rDNA band of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 by the gel documentation system. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 3: Phylogenetic tree of Junghuhnia sp. AK15. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 4: (a) Morphology of fungal colony, (b) Microscopic structure of Junghuhnia sp. AK15. [Click here to view] |

3.2. Frequency of Incidence Junghuhnia sp. AK15

Out of the total number of shortlisted yam tubers examined, an average of 15.91 ± 0.25 tubers showed infection by Junghuhnia sp. AK15, based on three replicates. Using the standard formula, the incidence of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 was calculated to be 27.44% [Table 1].

Table 1: Frequency of incidence of Junghuhnia sp. AK15.

| The number of tubers showed the presence of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 | Total number of tubers investigated | Frequency of incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 15.91±0.25 | 58 | 27.44 |

Results expressed as mean±standard deviation of three determinations

3.3. Pathogenicity Test

In the artificial pathogenicity test, 17 out of 150 inoculated yam tubers developed rot symptoms caused by Junghuhnia sp. AK15, corresponding to an infection rate of 11% [Table 2]. However, detailed examination revealed that each infected tuber exhibited an average rot severity of approximately 48% [Table 3]. All infected tubers displayed morphological characteristics and symptoms identical to those observed in naturally infected specimens. These symptoms included the formation of a dense, white, velvety mycelial mat on the tuber surface, accompanied by a sticky exudate ranging in colour from dirty white to light pinkish [Figure 5]. Panel et al. described various types of rotting symptoms in yams, including: crumbling of the underlying bark tissues in dry rot; softening of internal tissues with a brownish to pinkish discoloration in soft rot; and water-soaked, dirty white pulp with internal tissue softening in watery rot [31].

Table 2: Frequency of incidence of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 from the pathogenicity test.

| The number of tubers tubers infected by Junghuhnia sp. AK15 (W) | Total number of tubers taken for artificial inoculation of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 (Z) | Frequency of incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | 150 | 11.33 |

Table 3: Extent of rotting of yam tubers in pathogenicity test.

| Total Samples considered | Lesion diameter (cm) | Total surface area of tuber (cm) | Percentage of damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | 3.19±1 | 6.68±2 | 48±4.7 |

Results expressed as mean±standard deviation of seventeen determinations

| Figure 5: (a and b) Yam tubers showing rotten symptoms during the pathogenicity test. [Click here to view] |

3.4. Nutritional Study

Studies on the effect of three different solid nutrient media on the mycelial growth of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 revealed no significant variation in growth across the media [Figure 6]. In the comparative analysis, both PDA and SDA supported 100% mycelial growth, whereas CDA promoted 71.25% of the mycelial growth [Table 4].

| Figure 6: Growth of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 on different nutrient media. [Click here to view] |

Table 4: Assessment of growth response of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 to three solid nutrient media.

| Study organism | Mycelial growth rate percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Potato dextrose agar | Czapek dox agar | Sabouraud dextrose agar | |

| Junghuhnia sp. AK15 | 100 | 71.17±2.07 | 100 |

Results expressed as mean±standard deviation of three determinations

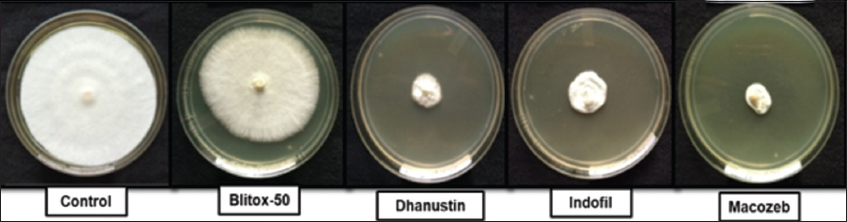

3.5. In-vitro Control of Junghuhnia sp. AK15

The antifungal activity of sixteen tested plant species, evaluated at three concentrations (20, 10, and 5 mg/mL), showed inhibition rates ranging from 18% to 100% against the isolated pathogen Junghuhnia sp. AK15. Notably, the petroleum ether extracts of A. scholaris and P. pinnata, as well as the methanolic extracts of A. conyzoides and A. carambola, achieved complete inhibition of fungal growth at 20 mg/mL [Figure 7]. Among the concentrations tested, 20 mg/mL consistently demonstrated the highest efficacy compared to 10 mg/mL and 5 mg/mL. Depending on the plant species, petroleum ether extracts were more effective in some cases, whereas methanolic extracts were superior in others. In contrast, synthetic fungicides exhibited varying levels of inhibitory activity [Figure 8]. Among the four fungicides tested, Mancozeb was the most effective against Junghuhnia sp. AK15, followed by Dhanustin, Indofil, and Blitox-50. Detailed inhibition percentages for both plant extracts and synthetic fungicides are presented in Table 5.

| Figure 7: In vitro antifungal activity of plant extracts (petroleum ether extracts of Alstonia scholaris). [Click here to view] |

| Figure 8: In vitro antifungal activity of synthetic fungicides. [Click here to view] |

Table 5: Antifungal activity of test plant extracts and synthetic fungicides.

| Sl. No. | Test plants | Common name | Family | Leaf extracts (mg/mL) | Inhibition of mycelial growth (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MET | PET | |||||

| 1. | Averrhoa carambola L. | Carambola | Averrhoaceae | 20 | 99.66±0.27 | 98.93±0.42 |

| 10 | 75.3±2.51 | 71.64±2 | ||||

| 5 | 43.64±1.52 | 35.64±1.52 | ||||

| 2. | Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. | Jackfruit | Moraceae | 20 | 97±0.47 | 98.66±0.54 |

| 10 | 62.65±1.52 | 63.91±4.58 | ||||

| 5 | 27.61±2 | 33.6±2.51 | ||||

| 3. | Alstonia scholaris (L.) R.Br. | Devil’s Tree | Apocynaceae | 20 | 99.46±0.23 | 100 |

| 10 | 70.63±2.51 | 72.96±2.64 | ||||

| 5 | 43.97±97 | 40.63±2 | ||||

| 4. | Ageratum conyzoides L. | Goat weed | Asteraceae | 20 | 100 | 98.13±0.38 |

| 10 | 68.28±3 | 71.65±1.52 | ||||

| 5 | 36.99±1 | 30.92±2.64 | ||||

| 5. | Abutilon indicum (L.) Sweet | Indian Mallow | Malvaceae | 20 | 95.22±0.95 | 98.63±0.55 |

| 10 | 65.31±2 | 55.62±2.51 | ||||

| 5 | 23.25±2.3 | 31.27±2.30 | ||||

| 6. | Cassia fistula L. | Golden Shower Tree | Caesalpiniaceae | 20 | 94.83±0.82 | 90.29±1.68 |

| 10 | 60.3±2.51 | 67.99±1 | ||||

| 5 | 33.27±2.51 | 33.64±1.52 | ||||

| 7. | Centella asiatica Urban. | Indian Pennywort | Apiaceae | 20 | 93.93±1.66 | 90.33±1.18 |

| 10 | 64.97±2 | 54.29±2.51 | ||||

| 5 | 32.95±2 | 27.66±0.5 | ||||

| 8. | Dillenia indica L. | Elephant Apple | Dilleniaceae | 20 | 94.66±1.08 | 91.66±0.72 |

| 10 | 68.92±4 | 55.65±1.52 | ||||

| 5 | 26.27±2 | 20.77±1.89 | ||||

| 9. | Eucalyptus globulus Labill | Eucalyptus | Myrtaceae | 20 | 92±1.24 | 98 |

| 10 | 54.31±1.52 | 63.31±2 | ||||

| 5 | 24.63±1.52 | 28.28±2 | ||||

| 10. | Haldina cordifolia (Roxb.) Ridsdale | Haldu | Rubiaceae | 20 | 92.59±1.24 | 91.58±1.25 |

| 10 | 52.97±2 | 53.29±2.51 | ||||

| 5 | 36.96±2 | 40.99±1 | ||||

| 11. | Justicia adhatoda L. | Malabar nut | Acanthaceae | 20 | 94.66±0.72 | 94±0.81 |

| 10 | 66.64±2 | 62.65±1.52 | ||||

| 5 | 34.6±2.51 | 41.29±2 | ||||

| 12. | Lawsonia inermis L. | Henna | Lythraceae | 20 | 95.63±0.25 | 90.33±0.72 |

| 10 | 63.96±2.64 | 53.57±3.78 | ||||

| 5 | 29.61±2 | 31.46±1.8 | ||||

| 13. | Murraya paniculata Jack. | Orange Jasmine | Rutaceae | 20 | 94.72±0.67 | 93.78±0.99 |

| 10 | 53.29±2.51 | 44.51±4.5 | ||||

| 5 | 33.64±1.52 | 26.98±1 | ||||

| 14. | Pongamia pinnata (L.) Panigrahi | Karanj | Papilionaceae | 20 | 94±0.81 | 99.66±0.27 |

| 10 | 71.32±1.52 | 74.65±1.52 | ||||

| 5 | 33.92±2.64 | 38.64±1.52 | ||||

| 15. | Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth. | Manila | Mimosaceae | 20 | 89.29±1.46 | 94.53±0.82 |

| 10 | 52.95±2.64 | 61.99±1 | ||||

| 5 | 22.57±2.51 | 25.9±2.64 | ||||

| 16. | Tamarindus indica L. | Tamarind | Caesalpiniaceae | 20 | 95.59±0.77 | 93.28±0.68 |

| 10 | 56.6±3.21 | 45.31±1.52 | ||||

| 5 | 22.6±2.08 | 18.94±1.73 | ||||

| Test fungicides (0.05 mg/mL) | Inhibition of mycelial growth (%) | |||||

| 1. | Dhanustin | 76.24±1.33 | ||||

| 2. | Mancozeb | 80.43±1.26 | ||||

| 3. | Blitox-50 | 17.79±0.24 | ||||

| 4. | Indofil | 72.5±1.17 | ||||

MET: Methanolic plant extracts; PET: Petroleum ether plant extracts

Results expressed as mean±standard deviation of three determinations.

4. DISCUSSION

Although 26 species of Junghuhnia have been identified worldwide to date [32], the isolate Junghuhnia sp. AK15 represents a novel strain within the genus. This study is the first to report Junghuhnia sp. AK15 as the causal agent of storage rot in yams (D. alata L.) in Odisha. Typically, Junghuhnia is known as a white-rot polypore fungus associated with wood decay [33], and has not previously been linked to tuber rot. However, earlier reports by Hood and Dick identified Junghuhnia vincta as pathogenic to Pinus radiata roots [34], whereas Taylor and Sale documented its association with roots of other coniferous and some dicotyledonous tree species [35]. The current isolation of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 from decaying yam tubers, corroborated through morphological and molecular identification, confirms a novel host-pathogen interaction. This finding broadens the known ecological niche and pathogenic potential of the genus, suggesting its adaptation to starchy, high-moisture substrates such as yam tubers.

In the present investigation, the isolate (Junghuhnia sp. AK15) was found to form a velvety white mycelial growth over the surface of infected yam tubers, producing dry rot symptoms. Traditionally, post-harvest rots in Dioscorea spp. have been attributed to a variety of fungal pathogens: Rhizopus nigricans, Sclerotium rolfsii, and Mucor circinelloides (soft rot); Aspergillus tamarii, Botryodiplodia theobromae, and Penicillium oxalicum (dry rot); and Erwinia carotovora (wet rot) [36].

Pathogenicity tests confirmed the ability of Junghuhnia sp. AK15 to initiate and propagate rot in healthy yam tubers under storage-like conditions, establishing it as a potential storage pathogen of economic importance. The study also assessed the in vitro antifungal efficacy of selected plant leaves as bio-control agents. Among the 16 tested species, A. scholaris, P. pinnata, A. conyzoides, and A. carambola exhibited strong antagonistic activity against Junghuhnia sp. AK15. This inhibitory effect is likely due to the presence of bioactive phytochemicals such as flavonoids, phenols, alkaloids, tannins, saponins, sterols, glycosides, anthraquinones, coumarin derivatives, leucoanthocyanidins, reducing sugars, simple phenolics, carbohydrates, fixed oils, terpenes, and phenylpropanoids [37-41].

This study contributes significantly to the understanding of post-harvest pathology in yams, especially in tropical and subtropical regions where warm, humid conditions favour tuber decay. The findings also offer promising avenues for developing eco-friendly, non-chemical management strategies. Biological control approaches are particularly advantageous for small holder farmers in regions such as Odisha, where yams are a key staple and income source, yet suffer considerable post-harvest losses due to rot. Even though the severity of infection by Junghuhnia sp. may be relatively low, its impact on tuber marketability is notable. Further research is essential to validate the efficacy of these bio-control agents under real-world storage and field conditions. Studies should explore the influence of environmental variables, formulation techniques, and application methods to ensure practical applicability. In addition, a deeper understanding of the life cycle and infection biology of Junghuhnia sp. yam tubers could guide the development of integrated and sustainable storage management practices.

5. CONCLUSION

The present study concludes that Junghuhnia sp. AK15 is responsible for causing storage rot in D. alata L. tubers under post-harvest storage conditions in Odisha, India. While the disease severity caused by the pathogen is relatively low, it remains significant as it reduces the market value of the tubers. Therefore, urgent attention is needed for its management. Both fungicides and plant extracts can effectively control the growth of this pathogen; however, fungicides pose risks to living organisms and have various side effects. In contrast, plant extracts, with no known adverse effects on the environment or health, offer a safer alternative. Employing plant extracts instead of chemical fungicides would be more beneficial for the ecosystem and human health, ensuring a sustainable contribution of yam crops to food security and the national economy.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was conducted at the P.G. Department of Botany, Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, with funding provided by the University Grants Commission (UGC), Government of India, New Delhi, through the Maulana Azad National Fellowship.

7. AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All the authors are eligible to be author as per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) requirements/guidelines.

8. FUNDING

This study received financial support from UGC-Maulana Azad National Fellowship for Minority students.

9. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

10. ETHICAL APPROVALS

This study does not involve experiments on animals or human subjects.

11. DATA AVAILABILITY

All the data is available with the authors and shall be provided upon request.

12. PUBLISHER’S NOTE

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

13. USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)-ASSISTED TECHNOLOGY

The authors declare that they have not used artificial intelligence (AI)-tools for writing and editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

REFERENCES

1. Liu Q, Liu J, Zhang P, He S. Root and tuber crops. In:Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food systems. Vol. 5. Netherlands:Elsevier;2014. 46-1.[CrossRef]

2. Scott GJ, Rosegrant MW, Ringler C. Global projections for root and tuber crops to the year 2020. Food Policy. 2000;25(5):561-97.[CrossRef]

3. Dioscorea alata Linn. Missouri Botanical Garden. Cambridge, MA, St. Louis, MO:Havard University Herbaria;2018. Available from:https://www.com/flora/of/[email protected]/eflora/web.

4. Fauziah F, Mas'udah, S, Hapsari L, Nurfadilah S. Biochemical composition and nutritional value of fresh tuber of water yam (Dioscorea alata L.) local accessions from East Java, Indonesia. Agrivita J Agric Sci. 2020;42(2);255-71. [CrossRef]

5. Nedunchezhiyan M, Sheela I, Jeeva ML, Kesava KH, Visalakshi Chandra C, Chintha P. Yams, Technical Bulletin No.101. India:ICAR-central tuber crops Research Institute;2023. 3

6. FAOSTAT. Food Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. Rome:FAOSTAT;2022.

7. Kumar S, Behera SP, Jena PK. Validation of tribal claims on Dioscorea pentaphylla L. Through phytochemical screening and evaluation of the antibacterial activity. Plant Sci Res. 2013;35(1&2):55-61.

8. Okigbo RN, Ikediugwu FE. Studies on biological control of post-harvest rot in yams (Dioscorea spp.) using Trichoderma viride. J Phytopathol. 2000;148(6):351-5.[CrossRef]

9. Panda D, Biswas M, Padhan B, Lenka SK. Traditional processing associated changes in chemical parameters of wild Yam (Dioscorea) tubers from Koraput, Odisha, India. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2020;19(2):268-76. [CrossRef]

10. Saklani S, Chandra S, Mishra AP. Nutritional profile, antinutritional profile and phytochemical screening of Garhwal Himalaya medicinal plant Dioscorea alata tuber. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2013;23(2):42-6.

11. Xie TY, Shen S, Hao YF, Li W, Wang J. Comparative analysis of microbial community diversity and dynamics on diseased tubers during potato storage in different regions of Qinghai China. Front Genet. 2022;13:818940. [CrossRef]

12. Norman DJ, Yuen JM, Bocsanczy AM. Threat of brown rot of potato and existing resistance. Am J Potato Res. 2020;97(3):272-7.[CrossRef]

13. Fan Z, Lin B, Lin H, Lin M, Chen J, Lin Y. g-aminobutyric acid treatment reduces chilling injury and improves quality maintenance of cold-stored Chinese olive fruit. Food Chem X. 2022;13:100208.[CrossRef]

14. Bonire JJ. Preventing yam rot with organotin compounds. Nigeria J Sci. 1985;19:145-8.

15. Ogaraku AO, Usman HO. Storage rot of some yams (Dioscorea sp.) in Keffi and environs, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Prod Agric Technol. 2008;4(2):22-7.

16. Akrasi KO, Awuah RT. Tuber rot of yam in Ghana and evaluation of some yam rhizosphere bacteria for fungitoxicity to yam rot fungi. Int J Agric Sci. 2012;2(7):571-82.

17. Ricci P, Coleno A, Fevre F. Storage problems in the cush-cush yam II. Control of Penicillium oxalicum rots. Ann Phytopathol. 1978;10(4):433-40.

18. Ogundana SK, Dennis C. Assessment of fungicides for the prevention of storage rot of yam tubers. Pestic Sci. 1981;12(5):490-4.[CrossRef]

19. Mugnucci JS, Kok CD, Santiago M, Green J, Hepperly PR, Velez H, et al. Yam (Dioscorea spp.) management for control of tuber decay. In:Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium of the ISTRC. Lima, Peru:International Potato Centre;1984. 607-13.

20. Plumbley RA, Cox J, Kilminster K, Thompson AK, Donegan L. The effect of mazalil in the control of decay in yellow yam caused by Penicillium sclerotigenum. Ann Appl Biol. 1985;106(2):277-84. [CrossRef]

21. Nnodu EC, Nwankiti AO. Chemical control of post-harvest deterioration of yam tubers. Fitopatol Brasil. 1986;1(4):865-71.

22. Thapa S, Thapa B, Bhandari R, Jamkatel D, Acharya P, Rawal S, et al. Knowledge on pesticide handling practices and factors affecting adoption of personal protective equipment:A case of farmers from Nepal. Adv Agric. 2021;2021:1-8.[CrossRef]

23. Shivpuri A, Sharma OP, Thamaria S. Fungitoxic properties of plant extracts against pathogen fungi. J Mycol Plant Pathol. 1997;27(1):29-31.

24. Gallian JJ. Management of Sugar beet Root Rots. United States:Pacific Northwest Extension Publication;2001.538.

25. Sambrook J, Fritsch ER, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning:A Laboratory Manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor NY:Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press;1989.

26. Edgar RC. MUSCLE:Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):792-7.[CrossRef]

27. Khatoon A, Mohapatra A, Satapathy KB. Studies on fungi associated with storage rot of carrot (Daucus carota L.) and radish (Raphanus sativus L.) in Odisha, India. Sch Acad J Biosci (SAJB). 2016;4(10B):880-5.

28. Saxena HO, Brahmam M. The Flora of Orissa, Orissa. Vol. 1-4. Bhubaneswar:Forest Development Corporation Ltd.;1994-1996.

29. Khatoon A, Jethi S, Nayak SK, Sahoo S, Mohapatra A., Satapathy KB. Evaluation of in vitro antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Melia azedarach L. Bark. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2014;9(6):14-7.[CrossRef]

30. Satish S, Mohan DC, Raghavendra MP, Raveesha KA. Antifungal activity of some plant extracts against important seed borne pathogens of Aspergillus sp. J Agric Technol. 2006;3:109-9.

31. Panel JA, Ekundayo JA, Naqvi SH. Preharvest microbial rotting of yams (Dioscorea spp.) in Nigeria. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1972;58(1):15-8.[CrossRef]

32. Yuan HS, Wu SH. Two new species of Junghuhnia (polyporales) from Taiwan and a key to all species known worldwide of the genus. Sydowia Horn. 2012;64(1):137-45.

33. Glazunova OA, Shakhova NV, Psurtseva NV, Moiseenko KV, Kleimenov SY, Fedorova TV. White-rot basidiomycetes Junghuhnia nitida and Steccherinum bourdotii:Oxidative potential and laccase properties in comparison with Trametes hirsuta and Coriolopsis caperata. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197667.[CrossRef]

34. Hood IA, Dick M. Junghuhnia vincta (Berkeley) comb. Nov., root pathogen of Pinus radiata. N Zealand J Bot. 1988;26(1):113-6.[CrossRef]

35. Taylor B, Sale PR. Horticultural produce and practice. In:White Crown Canker in Shelter Belts, Significance and Control. Vol. 131. 1st ed. Australia:AgLink;1980. 1-2.

36. Amusa NA, Baiyewu RA. Storage and market disease of yam tubers in South Western Nigeria. Ogun J Agric Res (Nigeria). 1999;11:211-25.

37. Ndacnou MK, Pantaleon A, Saha Tchinda JB, Mangapche EL, Keumedjio F, Boyoguemo DB. Phytochemical study and anti-oomycete activity of Ageratum conyzoides Linnaeus. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;153:112589.[CrossRef]

38. Verma PK, Tukra S, Singh B, Sharma P, Abdi G, Bhat ZF. Unveiling the ethnomedicinal potential of Alstonia scholaris (L.) R. Br.:A comprehensive review on phytochemistry, pharmacology and its applications. Food Chem Adv. 2025;6:100866.[CrossRef]

39. Khyade MS, Vaikos NP. Phytochemical and antibacterial properties of leaves of Alstonia scholaris R. Br. Acad J. 2009;8(22):6434-6.[CrossRef]

40. Jeelani I, Qadir T, Sheikh A, Bhosale M, Sharma SK, Amin A, et al. Pongamia pinnata:An heirloom herbal medicine. Open Med Chem J. 2023;17:1-14.[CrossRef]

41. Luan F, Peng L, Lei Z, Jia X, Zou J, Yang Y, et al. Traditional uses, phytochemical constituents and pharmacological properties of Averrhoa carambola L.:A review. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:699899.[CrossRef]